By Mustela Nivalis / The Libertarian Alliance

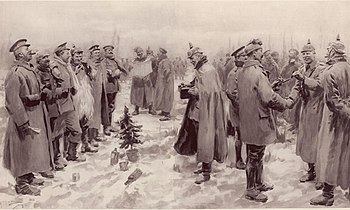

I personally find the 1914 Christmas truce on the Western Front remarkable for the following reason: using the famous image about the lamps going out across Europe, the Christmas truce can be viewed as the very last flickering of the dying pre-WW1-era. An era when borders were just lines on the map, when passports were limited to autocratic societies such as Russia (or rather, when autocratic societies were limited to places such as Russia). When money was worth its weight in gold and not in paper. When a word of honour still had weight. When the only contact most people in Britain had with the state was when they entered a post office. And when there still was – despite the rising nationalism and chauvinism – a strong sense of common European heritage. A large chunk of which being Christianity. Without it, the truce would not have happened.

Now, Sainsbury’s have discovered the power of this story – and that’s welcome news. It’s a good sign that a part of the ruling class is using images and ideas that run contrary to their beliefs and aims. It means they and their current religion of state idolatry are running out of steam. But I don’t want to talk about the advert. I want to talk about an earlier cinematic rendition, and about the truce itself.

In 2005, a feature film about this event was produced, entitled “Merry Christmas”, directed by Frenchman Christian Carion. It is of course not a precise record of what took place that evening and the following days. The narration has condensed, into one setting, events that took place at many parts of the front simultaneously. Altogether it is an adequate and fitting tribute to those soldiers who, defying orders and manipulations from above, and probably remembering the promise that it would all be over by Christmas, fraternised with the enemy, exchanged presents and even services such as haircuts.

As the film begins, three poems are recited, each by one schoolboy aged about 10. One French, one English, one German. The French poem talks about fetching back “the children of Alsace”. The German boy declares that Germany has “one enemy alone”, that being England. It is the English poem however that is really spine chilling and blood curdling. Here it is in full:

“To rid the map of every trace

Of Germany and of the Hun

We must exterminate that race

We must not leave a single one

Heed not their children’s cries

Best slay all now, the women, too

Or else someday again they’ll rise

Which if they’re dead, they cannot do.”

(See also this YouTube)

I have found no references to this poem other than in connection with the film. However, it looks authentic to me. It fits the propaganda, which in England was miles “better”, more effective, than anyone else’s in demonising the enemy. It’s also the kind of thing people said at the time, across Europe. “Gott strafe England” and all that.

Anyway, back to the film. I wouldn’t call it a great film. Neither is it bad though. If not great art, it is still the work of expert craftsmanship. It has a stringent story line. It has much good acting by good actors. It – mostly – avoids slipping into soppiness. Considering the subject matter, tragedy is balanced by some well placed doses of comedy that never tip into flippancy. It has a good score and fairly realistic images (although the mud is too dry) and sound. It is spoken in three languages: French, English and German. Actually, there is a fourth language, spoken by all during the Midnight Mass: Latin, which symbolises the dying common cultural/religious heritage. By the way, it is fitting that near the end a British (Roman Catholic) bishop preaches a very belligerent sermon (one which, according to Carion, was actually given in Westminster Cathedral in 1915). Outwardly a representative of Christianity, he is actually spouting chapter and verse of another religion, one that equates the state with God.

The film is well researched. In order to create more of a story, the narrative had to be exaggerated. But most elements are based on fact. For example in the film a woman opera singer has come to visit the German trench. She is the girlfriend of one of the soldiers, who himself is an opera singer. In the post-film interview available on the DVD, the director claims that some women, driven by love, actually made it to the fighting zone to meet their men (though not necessarily at Christmas). Also, there really was a famous – male – German opera singer (called Walter Kirchhoff) who visited the trenches that Christmas Eve and when he sang a French officer recognized his voice and applauded. The singer then went into No Man’s Land which is how in that section of the front the truce began.

Having said it is not a great film, it is so far the only feature film exclusively about the Christmas truce. Regardless of its qualities, it has one great merit: it brought the knowledge of this spontaneous peacemaking to modern day France and Germany.

It was the Germans who “started it” (the Christmas truce that is, because Christmas Eve is the big Christmas event over there), but – apart from the few participants who survived – they soon forgot about it, as did the French. It was the British who preserved the memory. And there is a very interesting reason for this, one pertaining to libertarianism. In the early months of the war, the press in Britain was not yet censored, and the soldiers’ letters were not spied upon by their superiors. (Or rather, in the words of film director Clarion, the British army was “not so efficient” in controlling the soldiers’ communication.) So, word got out. But only in Britain. France and Germany did not have a comparably strong liberal tradition and therefore found it easier to quickly drop any vestiges of it. So they forgot. The letters home to Britain, reporting the Christmas truce, were not intercepted. Once the families had received them, many got passed on to the papers, which ran the story.

So it was the Germans who set the truce going, rekindling once more, through ancient tradition, the extinguished lights of a more liberal, peaceful and civilised Europe. It was the British who preserved the memory of it, largely because it was here that liberalism lingered the longest. And it was a Frenchman who, with an entertaining and engaging film, opened up that memory to the world.

Some quotes from the film. https://www.youtube.com/embed/C24ww7GoFLA

Reprinted from The Libertarian Alliance.