By Matthew Vadum | Epoch Times

A looming battle at the Supreme Court may determine how social media companies moderate content. The nation’s highest court will hear challenges to laws in Florida and Texas that regulate social media content moderation.

Observers and activists on the left and right are watching the cases.

At stake is the right of individual Americans to freely express themselves online and the right of social media platforms to make editorial decisions about the content they host. Both rights are protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Republicans and conservatives were outraged when platforms acted in concert to ban President Donald Trump in January 2021, blocked a potentially election-altering New York Post article about Hunter Biden’s laptop on 2020, and silenced dissenting opinions about the origins of the COVID-19 virus, the treatments for the disease it causes, and the vaccines.

Steven Allen, a distinguished senior fellow at Capital Research Center, a watchdog group, said conservatives have long complained about their treatment on social media platforms.

“Imagine if you had a system analogous to what Facebook does, where if you say something on the telephone to someone that Facebook doesn’t like, or the phone company doesn’t like, and then they interrupt your call to say, ‘you know, experts disagree with that,’ … and then they wouldn’t let you continue to say what you wanted to say,” Mr. Allen said.

“People would be, of course, outraged.”

Facebook shouldn’t be allowed “to pick the ones it doesn’t like,” he told The Epoch Times.

Democrats and liberals, on the other hand, claim the platforms don’t do enough to weed out so-called hate speech and alleged misinformation, which they consider to be pressing social problems.

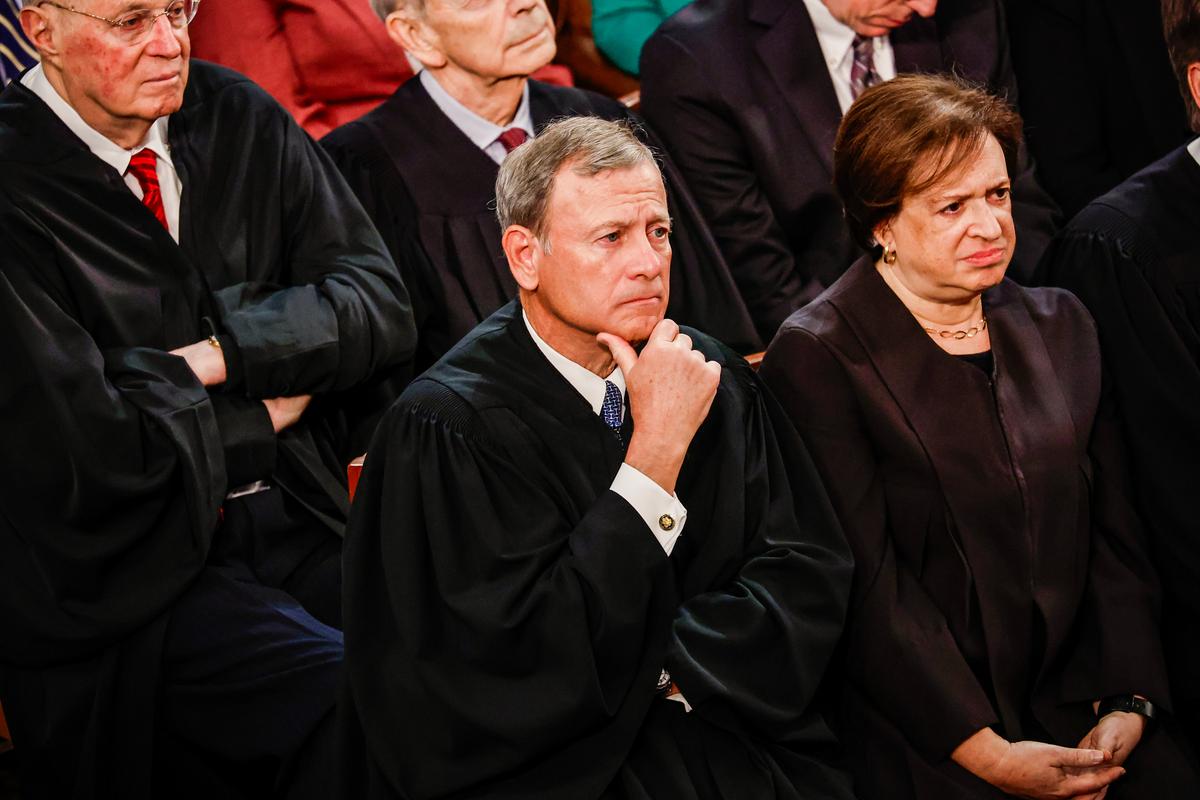

Moderators at the social media site Reddit filed a brief saying if the laws were upheld, the site would no longer be able to take down content threatening, for example, Supreme Court justices.

They provided a screen grab of a news article headline reading “Supreme Court’s John Roberts says judicial system ‘cannot and should not live in fear.’”

A person commented, saying, “We’ve got the guillotine, you’d better run.”

Responding to another article about the court, a user wrote, “Promoting violence is the only rational response, which is why the authorities don’t want you to do it.”

Two pro-gun control groups that filed briefs with the Supreme Court argue that social media companies must be allowed to combat hate speech, which they say contributes to “real-world gun violence.”

Douglas Letter, chief legal officer for the Brady Center for Prevent Gun Violence, said in the press release accompanying the brief that often “the perpetrators of mass shootings were radicalized online.”

“These online experiences are formative in germinating these deadly acts,” Mr. Letter said. “The Supreme Court must understand the deadly relationship between online content and real-world tragedy.”

Florida, Texas Laws Challenged

NetChoice, a coalition of trade associations representing social media companies and e-commerce businesses, challenged a Florida law that makes it a violation for a social media platform to deplatform a political candidate, punishable by a $250,000 per day fine.

The law also establishes restrictions on deplatforming other users and requires consistent application of moderation rules.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit halted part of the law and Florida appealed to the Supreme Court.

When signing the law in 2021, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, said it ensures Floridians “are guaranteed protection against the Silicon Valley elites.”

“Many in our state have experienced censorship and other tyrannical behavior firsthand in Cuba and Venezuela,” Mr. DeSantis said. “If Big Tech censors enforce rules inconsistently, to discriminate in favor of the dominant Silicon Valley ideology, they will now be held accountable.”

President Trump filed a brief with the Supreme Court in October 2022 as a private citizen, urging the court to hear the Florida case.

“Recent experience has fostered a widespread and growing concern that behemoth social media platforms are using their power to suppress political opposition,” his brief stated.

“This concern is heightened because platforms often shroud decisions to exclude certain users and viewpoints in secrecy, giving no meaningful explanation as to why certain users are excluded while others posting equivalent content are tolerated.”

Ohio, Arizona, Missouri, Texas, and 12 other states argued in a court brief that the internet is the modern-day public square and that social media platforms engaging in censorship “undermine the free exchange of ideas that free speech protections exist to facilitate.”

Suppression of ideas threatens “the development of important insights and discoveries, many of which begin as fringe views,” the brief states.

The 11th Circuit struck down part of the Florida statute, finding that “with minor exceptions, the government can’t tell a private person or entity what to say or how to say it.”

Even the “biggest” platforms are “private actors whose rights the First Amendment protects … [and] their so-called content-moderation decisions constitute protected exercises of editorial judgment.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit took the opposite tack, finding a Texas anti-deplatforming law constitutional and rejecting the “idea that corporations have a freewheeling First Amendment right to censor what people say.”

Both state laws require platforms to explain their content moderation decisions.

Legal Questions

The Supreme Court will attempt to answer whether the two state laws’ content-moderation restrictions and individualized-explanation requirements comply with the First Amendment.

Christopher Newman, an associate law professor at Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, predicts Section 230 of the federal Communications Decency Act of 1996 will come into play.

The provision generally protects internet service providers (ISPs) and companies from being held liable for what users say on their platforms. Supporters say the provision, sometimes called “the 26 words that created the internet,” has fostered a climate online in which free speech has flourished.

Section 230 says, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

The 5th Circuit looked at the section and said it means Congress believed ISPs, when publishing posts, are not speaking in their own right and therefore “don’t get to claim the mantle of First Amendment protection,” Mr. Newman said.

But Section 230 also says “ISPs are immune from liability for their decision to remove certain content, because it’s offensive, or obscene, or whatever,” Mr. Newman said.

The key goal behind the section was “precisely because the government wanted social media platforms to try to police and keep porn off of their sites,” he said.

“It’s clear that Congress wanted the social media platforms to have the right, without liability … to have it both ways … to both get protection from liability for bad things that they allow their users to post, while being immune from liability for being selective about what they allowed.”

The common carrier doctrine, which has its origins in England, is also likely to come up in oral arguments, Mr. Newman said.

The basic idea behind common carrier status is that it’s “almost analogous to treating somebody as a utility,” which gives the government power to regulate it in the public interest, he said.

Being considered a common carrier gives the government authority “to impose basic non-discrimination obligations … [like] the ones that they impose on a public utility. You don’t just get to arbitrarily exclude people from the platform, and you have to give people service on equivalent terms,” Mr. Newman said.

Both of the state statutes ban certain kinds of discrimination by the platforms and “impose fairly burdensome disclosure requirements, like basically, every time you make a content moderation decision, you have to publish an opinion explaining why you did it,” he said.

“Imagine being a social media company that’s dealing with billions of posts a day, and having to make content-moderation decisions at scale.

To have to write an explanation justifying each moderation decision would be “prohibitive,” Mr. Newman said.

Jim Burling, vice president of legal affairs for the Pacific Legal Foundation, a national nonprofit public interest law firm that challenges government abuses, said Americans are justifiably angry about the conduct of social media platforms.

People who express views that call into question “progressive dogma” have been kept off social media and many users have been booted from YouTube, Mr. Burling told The Epoch Times.

“So a lot of people are legitimately upset about social media companies keeping them off. And the icing on the cake, of course, is what we’ve learned recently of the United States [government] putting extreme pressure on the social media companies to censor.”

On Oct. 20, the Supreme Court granted the petition in Murthy v. Missouri. The court will look at whether the Biden administration ran afoul of the Constitution when it pushed tech companies to delete what it deemed false or misleading content about COVID-19 and the disputed 2020 presidential election.

Mr. Burling said the Texas and Florida cases have reminded him of the Fairness Doctrine, a 1949 policy of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that forced holders of broadcast licenses to present differing viewpoints on controversial issues.

The policy was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1969 but rescinded by the FCC in 1987.

“Every now and then there are people who want to reimpose some sort of Fairness Doctrine,” he said, adding that the courts “have never actually firmly struck it down.”

To what extent can a government–state, federal, or local—regulate expression on a social media company?” Mr. Burling said.

“That is going to be the $64,000 question.”

Recent Cases

The Supreme Court weighed in on social media issues earlier this year.

The court sidestepped the issue of platforms’ liability shield for user content in its May 18 rulings in Twitter Inc. v. Taamneh and Gonzalez v. Google LLC.

Taamneh concerned a Jordanian man killed in an ISIS terrorist attack in an Istanbul nightclub. The man’s family argued Twitter, Facebook, and Google should be held liable because they didn’t do enough to take down ISIS videos that they assert aided the terrorist group.

In Gonzalez, the family of a U.S. woman killed in an ISIS attack in Paris sued, claiming that Google, owner of YouTube, was liable under the federal Anti-Terrorism Act for aiding ISIS recruitment efforts by allegedly using algorithms to steer users to ISIS videos.

The Supreme Court unanimously sided with Twitter, Google, and Facebook, finding in the two cases that a connection between the Silicon Valley giants and the deaths of their relatives had not been proven, so it wasn’t necessary to reach the Section 230 issue.

The Supreme Court also heard two cases, O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier and Lindke v. Freed on Oct. 31.

The legal issue is whether a public official is engaging in governmental action subject to the First Amendment when blocking someone from accessing the official’s social media account.

In the first case, two elected local school board trustees in California, who used their personal Facebook and Twitter accounts to communicate with the public, blocked parents they claimed were spamming them.

The parents countered they were communicating in good faith.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled for the parents, finding the elected officials using social media accounts were participating in a public forum.

In the second case, a city manager in Michigan who used Facebook to communicate with constituents blocked people who criticized the municipality’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit ruled for the official, holding he was acting only in a personal capacity and that his activities did not constitute governmental action.

President Trump was sued in 2017 by the Knight First Amendment Institute and seven individuals whom he had blocked on Twitter. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit agreed with the individuals, finding the then-president had violated the First Amendment.

In April 2021, almost three months after President Trump was banned from Twitter, the Supreme Court ruled the controversy was moot because the president had left office. Elon Musk subsequently purchased Twitter and reversed the ban.

Oral arguments in Moody v. NetChoice LLC and NetChoice LLC v. Paxton are expected in the spring.

Decisions are expected by June 2024.