The New York Times

Foreign aid isn’t just charity. It’s power. That was the original idea behind the United States Agency for International Development, which J.F.K. set up in the early 1960s to win the support of developing countries that might have otherwise drifted into the Soviet sphere. Elon Musk dismantled it in recent weeks. For now, most of its work has stopped and its worldwide staff has been called home.

President Trump and his team have criticized a few progressive State Department programs, like a Colombian opera about a trans character and a D.E.I. music event in Ireland. But the core of U.S.A.I.D.’s mission has been helping the world’s poor, and it was a means to an end. “You have to understand,” a veteran American diplomat told me, “we didn’t do this work because we’re all a bunch of bleeding-heart liberals. We did it for influence.”

In today’s newsletter, we’ll examine that effort — and the results it got.

Good works

How do you measure influence abroad? Experts have come up with the acronym DIME — diplomacy, information, military, economic — to describe the traditional levers of power. U.S.A.I.D. covers every aspect but the military one.

When I was covering East Africa, I ran into U.S.A.I.D. all the time. I saw sacks of wheat stamped “U.S.A.I.D. From the American People” trucked out to famine areas in Somalia. I saw thin-walled, U.S.A.I.D.-funded schools in South Sudan giving kids their first crack at education. I met bright young people who won scholarships to study in the U.S., planting little seeds of pro-American sentiment everywhere. I wrote about American aid being stolen and misused, too, and there’s no doubt that U.S.A.I.D. was ripe for reform.

There is a long-running debate about the effectiveness of foreign aid. Scholars have criticized it for failing to reduce poverty or stimulate economic development. There are infamous examples of expensive disasters — like a Norwegian-backed frozen fish factory in a very hot part of Kenya. But that was in the 1980s. These days, most aid for Kenya goes toward food security and health programs, which even critics acknowledge save lives.

The billions Washington spent there has paid off. Over the years, Kenya has become one of America’s most reliable allies in the developing world. It has served as an operations center for antiterrorism strikes in the region. It buys more American goods like aircraft parts each year. As other African nations cozy up to Russia, a Kenyan diplomat delivered one of the most eloquent and rousing speeches at the United Nations condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Now, foreign aid is not the only reason for this. Kenya has always been close to the West. But there is no doubt that many Kenyans are grateful for the American help and that the U.S.-Kenya relationship gets tighter each year.

The aid Kenya was relying on has vanished, at least for now. That could leave Kenyans feeling burned, undermining the soft power the United States has spent decades — and billions — cultivating. Already, Beijing is desperate to find allies in Africa, said Michael H. Chung, an infectious disease doctor from Emory’s Global Health Institute who has worked in Kenya. “We will be ceding one of the world’s most economically dynamic and youthful regions to China,” Chung lamented.

Consequences

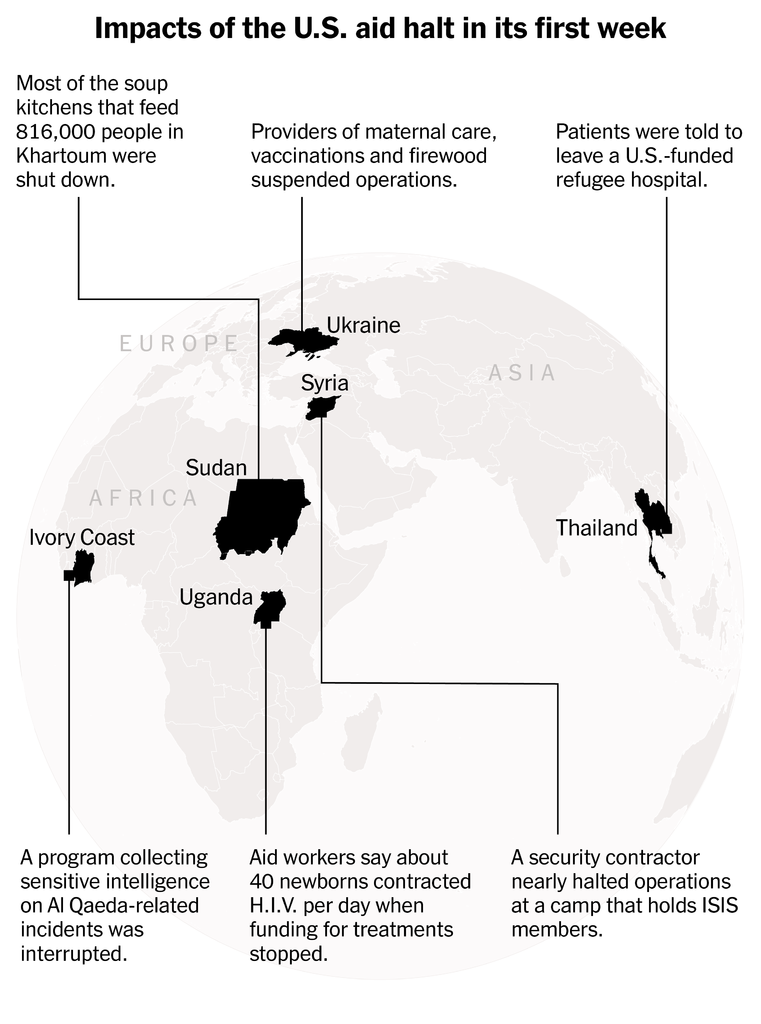

The abrupt end to $44 billion in aid has been chaotic. And wasteful. Hundreds of millions of dollars of food may soon rot in the ports and warehouses where it is stuck. The battle against deadly disease, too, could suffer. Until last month, the United States provided medication for 20 million H.I.V. patients. The secretary of state said that work should continue, but now the program is in disarray. Without the meds, those lives are at risk and so is the effort to stop the spread and mutation of H.I.V.

The ramifications are clearly not just humanitarian. Business executives fret that aggrieved nations might make it harder for Americans to get travel or work visas. Or they might cast more votes against American interests at the United Nations. Anti-Western sentiment in West Africa eventually calcified into official pro-Russia policies. American and French troops have been kicked out of one country after another. This is how it works. There may not be a decisive break but a steady, inexorable erosion of support.

Some of Trump’s allies argue that U.S.A.I.D. was an irritant in the relationship with authoritarian countries like Hungary, for example. Viktor Orban, its strongman leader, often complains about U.S. support for pro-democracy groups.

The view at U.S.A.I.D. was that influence is won not just from governments, but also from people — who may eventually take back their governments. Ukraine and Georgia are countries where aid supported Western-leaning democratic movements that eventually took power.

In exchange for the freeze Elon Musk has imposed, the United States will save less than 1 percent of its budget. If those savings are put toward renewing or expanding Trump’s tax cut, which seems likely, those billions will flow directly from the mouths of the world’s poorest into the pockets of the world’s richest.

Marco Rubio, the secretary of state, said that every aid dollar must answer three questions: “Does it make America safer? Does it make America stronger? Does it make America more prosperous?” U.S.A.I.D., foreign policy experts say, answered all three.