Florida’s Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd believes that no crime should go unpunished.

POLK COUNTY, Fla.—Across a six-decade career, beginning as a 16-year-old ambulance driver to his ascension as America’s most renowned lawman, Grady Judd has made one thing clear.

He’s that guy, that old-school sheriff whose tough-talking press conferences garner national attention, but he’s also a lifelong student of integrating new-school techniques with emerging technologies, a pioneering innovator in administration, and a conscientious mentor who lives as he leads.

And so, on this April afternoon, Mr. Judd, 70, is looking back on 54 years in public service by doing what he’s always done, looking forward.

He’s prioritizing goals for his sixth term as sheriff of Polk County, a 2,000-square-mile sprawl of Central Florida sawgrass savannah between Orlando and Tampa that’s doubled in population in a decade.

His new term officially begins in January but it actually began the February day he filed to run, instantly clinching his third-straight unopposed re-election.

There’s plenty of time to talk about the past but, right now, he told The Epoch Times, “There’s plenty of work to do over the next four years in keeping crime down.”

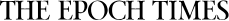

Mr. Judd said the 1,800-employee Polk County Sheriff’s Office (PCSO), which includes 1,100 deputies, 1,330 vehicles, and a 2,500-bed jail with a $236 million budget, will be busy doing just that every day, all day, while taking on two initiatives.

He is launching a program to help keep the mentally ill out of jail, a chronic national urgency that defies easy solutions, while training a unit to combat the next great global crime challenge: artificial intelligence (AI).

A pressing focus everywhere, he said, is to “reduce the need” for first-responders to be roadside therapists in protecting the mentally ill from themselves and others, and to find alternatives to using jails as primary—and often only—sources of medication for many with mental health issues.

As a newly-minted deputy in 1974, he recalls, those arrested exhibiting mental problems were housed in a regional hospital where inmate patients were treated.

“Fast-forward to today” and his deputies don’t have that option, Mr. Judd said.

“The state and federal government did away with mental hospitals. So where did those mentally ill end up? They ended up in prison, in county jail lockups. They ended up underneath overpasses, sleeping behind buildings, out in the woods.”

Institutional options narrowed as pharmaceutical solutions expanded, he said. Advocates for the mentally ill argued, “They have a constitutional right not to be incarcerated’ and, ‘Oh, we have these new medicines. They just have to take the medicines.’”

Good concept, Mr. Judd said, bad plan.

“Where do we find them to give them their medicines? And, oh, you’re not going to provide medicines? How’re they going to afford it? It’s very expensive” especially for mentally ill people living “out in the woods,” he said.

So he has a plan—and $1 million in seed money from Polk County commissioners to provide court-mandated medications for itinerant offenders.

“We’re in the infant stages of that. We’ve gotten total cooperation from everyone,” Mr. Judd said of a coalescing coalition that includes providers, the courts, state attorney’s office, public defenders, and advocates for the mentally ill. “That’s pretty remarkable that everybody says, ‘Yes, let’s do this.’ It’s a win-win for everyone.”

In an age of polarity, a “win-win for everyone” is a rare air that Grady Judd exudes.

He’s doing what he’s wanted to do since he was 4, what he believes God put him here to do, to protect the place where he was born, raised, and lived his whole life, where he married his high school sweetheart and raised two sons, where he pioneered crime-fighting tactics in a changing world while never wavering from fundamental truths such as right from wrong, good from bad.

In exchange, Polk County got the right sheriff at the right time, a leader to meet the challenges posed by growth as it evolved into an urbanizing I-4 corridor where 100,000 new people have arrived each of the last three years.

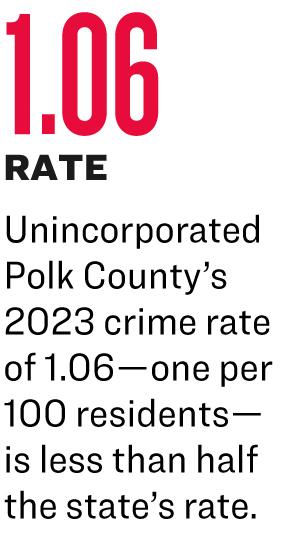

And yet, unincorporated Polk County’s 2023 crime rate of 1.06—one per 100 residents—is less than half the state’s rate and lowest since the metric was created in 1971, lower than when it had three times fewer people and 88 percent less than when it had half as many people.

A “win-win” for all—except criminals.

“I’m blessed to live God’s mission for me,” Mr. Judd said. ”All I’ve ever wanted to be was sheriff—the sheriff of Polk County.”

Sheriff-in-Waiting

Raised in a Lakeland subdivision of cinder block homes without air conditioning, Mr. Judd shows office visitors a black-and-white 1954 photo of him sitting on an uncle’s lap. His uncle was White County, Tenn., Sheriff Joe McCoy, but it was Grady Judd wearing the sheriff’s star.

He was the cop when playing ‘cops and robbers’ with childhood friends, grew up watching TV shows such as ‘Dragnet’ and ‘The Andy Griffith Show,’ and was scanning police radio frequencies and mastering codes at 12.

As he told The Epoch Times in November 2023, his father, a Cadillac dealership service-manager, was a church deacon. “I was raised in the church,” he said. “We were sometimes the first to arrive and the last to leave.”

Faith, his “guiding light,” compelled him to be a relentless teenager in informing the sheriffs office he’d be joining them soon and someday be the boss.

As a high school junior in 1970, he was hired as a $1.65-an-hour ambulance attendant in Winter Haven. He helped deliver a baby at 16 and at 17, convinced the notoriously recalcitrant musician George Jones, in a drunken rage, to get into his ambulance, later admitting he had no idea who the world-famous country star was.

After going to high school by day, finishing his ambulance shift at night, Mr. Judd hung out at the sheriff’s office, effectively forcing them to hire him two months after graduation as a dispatcher despite a minimum-age requirement of 21.

He remembers July 21, 1972, a humid, storm-stirred Friday night, his first shift at Bartow’s Hall of Justice, which “housed the entire justice system” and “one teletype computer.”

Richard Nixon was president, Reuben Askew was governor of Florida, gas was 34 cents a gallon, ‘The Godfather’ was a box office hit, Bill Withers’ ‘Lean On Me’ topped the charts.

Two months later, Mr. Judd married his fiancé, Marisa, also 18 and also newly hired at a municipal finance department. They lived on combined salaries of $550 a month. They’ve been together since.

When legislators waived the 21-year-old requirement to be a law enforcement officer. Mr. Judd convinced Sheriff Brannen—the icon of his youth—to send him to the state’s police academy. Just before he turned 20, he was sworn in as the first-ever PCSO deputy under 21.

He hit the road as a 19-year-old deputy in February 1974 in a green-and-white Ford Galaxy and a pistol his father had to buy because state law precluded him from doing so. Nevertheless, as Mr. Judd says, “The rest is history.”

The Showman Sheriff

Mr. Judd advanced to corporal at 22, sergeant by 23, lieutenant at 25. He was a homicide captain at 27 managing a $1 million budget and 44 employees, a major at 34, survived 1980s political tumult to emerge as a colonel who spearheaded the agency’s 1990s’ modernization.

After serving under five sheriffs, Mr. Judd was elected sheriff with 64 percent of the nonpartisan vote in 2004. He was reelected in 2008 and 2012 with 96 percent of each tally. In 2016, 2020, and 2024, he ran unopposed.

Over the last 20 years, the gregarious Mr. Judd has risen to national prominence with a “greatest hits” parade of blunt press conference and social media commentary, including his 2006 response to why a man who’d killed a deputy and K-9 dog was shot 68 times: “That’s all the bullets we had or we would have shot him more.”

Actually, nine officers from three agencies shot the gun-waving killer 89 times and had more than 400 unexpended rounds on them, according to an investigation by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

The message, nevertheless, was clear.

Mr. Judd made national news again in 2010 when his detectives purchased Phillip Greaves’ “The Pedophile’s Guide to Love & Pleasure,” asked him to autograph it (to show it had been in his hands), and mail it to them.

After detectives received the book in the mail, they flew to Colorado, arrested Mr. Greaves—when no agency would—flew him to Polk County, and charged him with selling obscenity harmful to a minor. He remained in jail for four months until pleading no contest to time-served, probation, and court-mandated mental health counseling.

Mr. Judd’s quips have garnered a massive social media following for PCSO, including 100 million Tik Tok views.

They can be seen on T-shirts and are immortalized in a rap video, ‘Ducking Grady.’ His 2–3 minute “morning briefings” have 105,000 daily subscribers and PCSO’s 700 YouTube videos have been viewed 14.6 million times.

He’s most in his element when orchestrating stings. Among recent notables are Operation Swipe Left for Meth, a six-month investigation into meth-dealing on dating apps that netted 68 arrests in January 2022; October 2023’s Operation Straight Outta Compton, in which 10 kilograms of fentanyl was seized and three people arrested, including two Sinaloa Cartel traffickers in the country illegally; and Operation March Sadness 2024, which resulted in 228 prostitution-related arrests and “the rescue of 13 potential human trafficking victims.”

Mr. Judd has served in many peer-elected leadership posts, such as Florida Sheriffs Association president (2013–2014), and Major County Sheriffs of America (2018–2019) president, and been appointed to numerous boards.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who Mr. Judd vociferously supported in his failed 2024 presidential bid, appointed him to the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission (2018–2023).

President Donald Trump, who he openly backed in 2016, supported without fanfare in 2020, and rarely directly mentions now—segueing instead into criticism of President Joe Biden—appointed him to the Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2020–2023).

While the “win-win” confluence of self-determination and faith are the motivations, Mr. Judd’s passion for education is the fuel driving his interests in technology, innate organizational talent, and gregarious personality that demonstrates media savvy, is a potent crime-fighting tool.

Old School, New Tools

While a dispatcher, Mr. Judd convinced Lakeland Community College to create a police science program, eventually earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Rollins College under the now-defunct LEEP (Law Enforcement Education Program).

“It changed the way I looked at the world. It changed the way I policed. It changed the way I rationalized and thought about and interviewed and talked to people,” he said. “It gave me more tools in my toolbelt.”

Mr. Judd convinced “a sheriff a long time ago that we needed to fund education since no one else was” to equip deputies with academic fundamentals while learning the latest in crime-fighting techniques, tactics, and technologies.

“I knew how much it helped me and we wanted to professionalize the organization,” he said. “As time went on, a few more people voluntarily took their classes and got degrees” until it became an unofficial standard for advancement.

Upon election, Mr. Judd made college degrees the official standard for promotion. “If you don’t have a bachelor’s degree, you can’t be a sergeant or a lieutenant. You can’t be a captain, a major, without a master’s degree,” he said.

He requires PCSO officers “go to ‘finishing schools,’” such as the FBI National Academy, Southern Police Institute, and Northwestern University’s Center for Public Safety.

Constant exposure to leading crime-fighting theories and techniques have translated into numerous programs and tactics Mr. Judd—and now others—have applied in Polk County.

He recalls a mid-90s seminar taught by then-New York City Police Department Commissioner Bill Bratton and his deputy commissioner, Jack Maples, who created the CompStat methodology that would become PCSO’s standard of operation.

“Crime was out-of-control in the subways in New York, rapes, robberies, murders, you know, beat-downs,” Mr. Judd said. “Bill Bratton and Jack Maples, they said, ‘Okay, here’s what we’re going to do to: we’re going to stop the toll-jumpers.’

That drew criticism and mockery.

“Well, guess what happened when they stopped the toll-jumpers?” he said. “Murders went down, robberies went down, everything went down because the morons committing the minor crimes were also the ones committing the major crimes.”

That’s why there’s no tolerance for minor crimes in Polk County. “I brought that philosophy back here and we adopted it and our crime rate went down like 88 percent” in the late ‘90s.

There’s a “remarkable” statistical correlation between enforcing “minor” crimes and preventing “major” crimes, he said, noting “our crime rate is remarkably low because it’s where you set the bar.

“We don’t allow people to shoplift and get away with it,” Mr. Judd said. “We lock them up. So, if you get caught shoplifting in Polk County, you’re going to walk out of the store in handcuffs and you’re going to jail. Every time.”

The zero-tolerance ideology is supplemented with technological advances Mr. Judd installed, such as the Proactive Community Attack on Problems (PROCAP) initiative, a “data-driven community policing program” focusing on where crimes occur on a daily basis.

Among organic programs Mr. Judd created is PCSO’s National Innovation Academy, “a dream of mine I’ve had for a long time” in partnership with Polk State College that “teaches the foundational leadership and administrative qualities and techniques” others do but “our academy is STEM-based and focuses on technology.”

Innovation is a constant process, he said.

“We’re updating our computer system right now,” he said. ”We have a 911 system we just introduced where a deputy in the field can ‘geofence’ his work area. When someone dials the 911 emergency center, we can hear the transmission in the car and start our response even before we’re dispatched.”

Teaching to Learn to Lead

He may be an old school lawman by divine inspiration, but Mr. Judd is a new school teacher because he learned how to be one, and a modern day leader because he learned how to be one.

And because he did so, he now teaches others how to lead.

Before becoming sheriff, Mr. Judd taught 23 years as an adjunct professor at Florida Southern College and University of South Florida. He “can’t carve the time out” to do so anymore, but he’s still teaching.

“My basic philosophy now is as a coach,” Mr. Judd said. About once a month, he greets “our new class of employees” with a lecture that lays it all out.

“I say, ‘Hello to working with the sheriff’s office. You’ve got to be honest, ethical, and moral all-of-the-time. You’ve got to deliver customer service with a sense of urgency all-of-the-time. You’ve got to talk to people and treat people like you’d want your mother to be talked to and treated all-of-the-time.’

“‘This is a job to resolve conflict,’” he said. “‘When people can’t resolve issues on their own, they call law enforcement and we’re mandated to resolve it. There will be occasions where we have to use protective force. But make them make us do that.”

Assured accountability assures accountability, he said.

“Do we hold people accountable? Absolutely,” Mr. Judd said. “But we don’t pull rabbits out of hats. Everybody knows what we expect here the day they come to work here.”

He’s “read everything when it comes to belief systems and processes and motivations” and found what he’s always known to be true.

“You have to love your work, love your workforce, before you can lead them anyplace,” Mr. Judd said. “If you don’t love them, if you don’t believe in them, if you don’t trust them, then why should they believe in you and trust you? So, I trust the men and women of the Polk County Sheriff’s Office first.”

Mr. Judd will soon have “a new class” to inspire. They’ll join a law enforcement agency with a waiting list of recruits when many police agencies are struggling to hire.

He’s proud of that.

During a 90-minute tour of PSCO’s headquarters and adjacent Emergency Operations Center, where 25 agencies field 911 calls in a high-tech nexus surrounded by cow pastures and ponds, he made a point of showing “inspirational art” featuring employees and deputies, staff wildlife and landscape photos—he’s an avid photographer—and a wall honoring those who’ve made their careers with the PCSO.

He’s proud of that, too.

Not many served long enough to qualify for retirement when he joined 52 years ago, he said. Now, they come to learn, to lead, to join an agency he molded, and, he beams, to stay because it’s a good job in a good place protecting good people.

“I’m just the coach now. They do the heavy lifting,” Mr. Judd said. “I’ve always got their back. But they’ve got to do what’s right and they’ve got to care about this community.”