By John Carney & Alex Marlow

As the evidence keeps pouring in that the U.S. is still mired in an inflationary economy, the possibility that the Federal Reserve will be forced to increase interest rates can no longer be ignored.

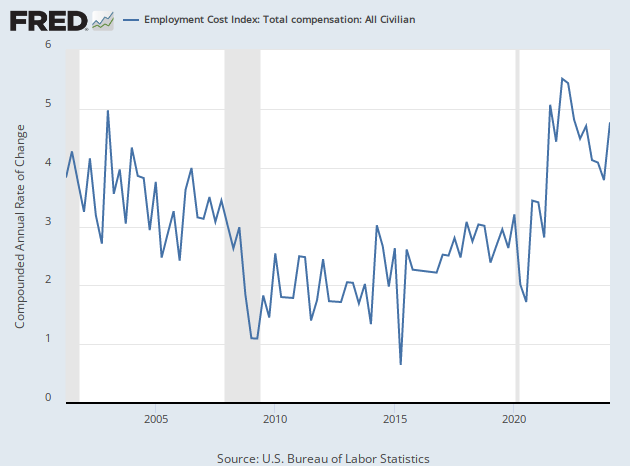

Compensation costs for public and private sector employers climbed 1.2 percent in the first quarter, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Tuesday. That’s an acceleration from the prior quarter’s 2023 pace of 0.9 percent and the largest increase since the second quarter of 2022.

If we annualize the first quarter increase, compensation costs rose at a pace of nearly 4.8 percent. That is more than double the 2.2 percent average annualized pace in the quarters in the decade before the pandemic. By most estimates, gains in the employment cost index (ECI) significantly above three percent are inconsistent with the Fed’s two percent inflation target.

The rise in employment costs once again caught analysts offsides. Many remain wedded to the narrative of a “softening” labor market in which unemployment creeps slowly up, job openings decline, and compensation costs moderate.

An Overheating Labor Market

The data, however, is running in the opposite direction. The economy added 256,000 workers onto payrolls in January, 270,000 in February, and 303,000 in March. For those of you in the back of the classroom, that is an average of 276,000, a big jump from the 212,000 in the final three months of last year.

Jobless claims, usually a leading indicator for softness in the labor market, have gone nowhere. In a series that is notoriously volatile week-to-week, there’s been a spooky placidity. For eight out of the past nine weeks, we’ve been within 3,000 claims of 210,000. In five of those weeks, we had exactly 212,000.

The unemployment rate fell in March to 3.8 percent, exactly where it was from August through October of last year. It ticked down to 3.7 percent in November, December, and January. When it rose in February to 3.9 percent, many economists were quietly relieved (you aren’t supposed to celebrate rising unemployment), but that did not last.

The expectation for the April employment report is for 250,000 jobs. If that’s right, the three-month moving average will fall to a still sky-high 274,000. Barring downward revisions to earlier months, any reading above January’s 256,000 will mean that the three-month average will increase. Goldman Sachs just said that they expect 275,000 jobs, which would yank the three-month average up to 283,000.

A Violent Shift in the Labor Market and Inflation Data

This was not how things looked like they were going to go just a few months ago—at least in the view of establishment economists and Wall Street. While Breitbart Business Digest was warning that the economy was accelerating, the labor market was gaining steam, and inflation had stopped declining and was showing signs of reaccelerating, most economists had signed on to the “soft landing” thesis where inflation would come down without much damage to the labor market or growth.

Here’s Jerome Powell speaking at the January Federal Open Market Committee press conference, which happened to occur on the same day the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that fourth quarter ECI had risen just 0.9 percent.

The, the economy is broadly normalizing, and so is the labor market. And that process will probably take some time. So wage setting is something that happens—it’s, it’s—you know, probably will take a couple of years to get all the way back. And that’s okay. That’s okay. But we do see—you saw today’s ECI reading—you know, the evidence is that, that wage increases are still at a healthy level—very healthy level—but they’re gradually moving back to levels that would be more associated—given, given assumptions about productivity, are more typically associated with 2 percent inflation. It’s, it’s an ongoing process—a healthy one— and, and, you know, I think we’re, we’re moving in the right direction.

We’ve now gone in the opposite direction, also known as the wrong direction.

On February 1 of this year, we warned that the data were indicating to us that the Fed would likely not be able to cut until November. The futures market at the time was pricing in a 95 percent chance of a rate cut at the May meeting (the one occurring right now).

“There’s a non-trivial chance that the Fed does not get to cut rates at all this year. As we have been warning, there are plenty of reasons to worry that inflation will accelerate. If it does, that could take Fed cuts off the table for the rest of the year,” we wrote.

A week later, we warned that an acceleration of inflation could mean that the Fed’s next move could actually be an increase instead of the cut that Wall Street is so certain is coming.

We got the acceleration of inflation we feared. The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index that the Fed says it watches exploded higher in the first quarter of this year, clocking in at an annualized rate of 3.4 percent, up from 1.8 percent at the end of last year. Core PCE inflation rose at a 3.7 percent annualized rate, up from two percent.

Wall Street still expects a rate cut, although the futures market now agrees with our analysis from three months ago that the Fed may hold off until the November meeting. Fed officials very likely also believe that they will cut rates at least once this year, although we think there is a possibility that the next summary of economic projections may show an increasing number of Fed folks think they may have to wait until next year.

But where is the disinflation going to come from that would justify a cut? The job gains and compensation cost increases suggest inflation is deeply embedded. The expiration date on the supposedly variable and lagged effects of the last Fed hikes has come and gone. Fuel prices are rising rapidly—and we’re not even in the summer driving season yet. The massive migration across our border is fueling excess government spending that translates quite directly into demand for housing, food, and other services, more than offsetting any supposed benefit from additional workers.

It would be extremely unwise for the Fed to wait until next year to start to indicate that its next move might be a rate increase. If voters give control of the White House back to Donald Trump, a sudden Fed pivot to rate hikes would look extremely political and likely endanger the independence the central bank so zealously guards. Far better to at least start talking about the possibility earlier.

In short, the Fed should start talking about rate increases as soon as possible. It’s probably too much to expect Jerome Powell to take such a hawkish stance at tomorrow’s press conference. But a prudent Fed would not wait much longer.