By Michael Curtis / American Thinker

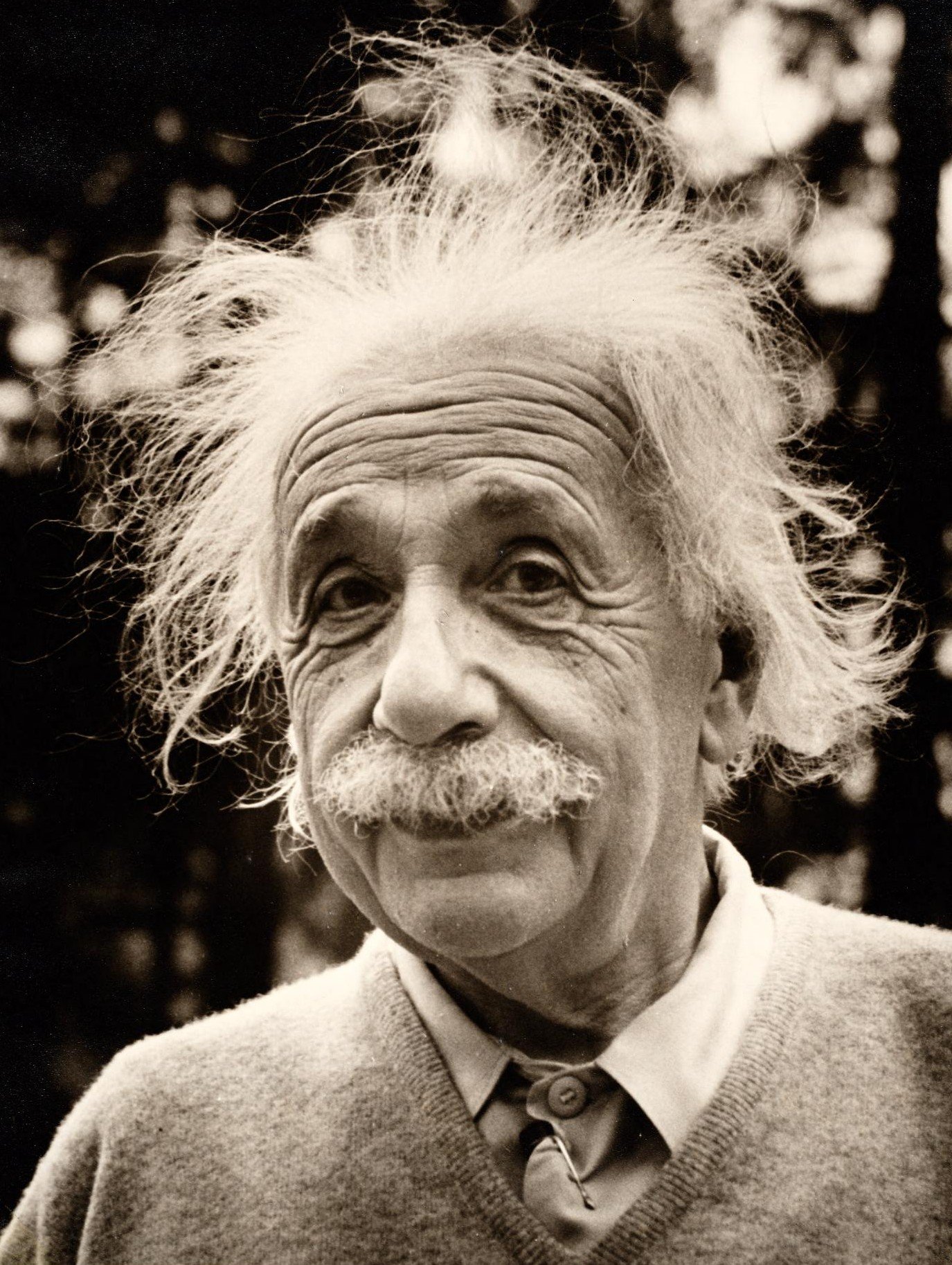

Albert Einstein, the pipe-smoking individual with unkempt hair and rumpled clothes, the violin player who loved Mozart’s music, the resident in a very modest house on Mercer Street in Princeton, New Jersey, is universally regarded as one of the great personalities of the 20th century. For many he is the greatest mind of his time, and for others the greatest Jew of the last century.

What is now publicly added to the story of his legendary career is a previously unknown letter, to be auctioned on April 18, 2016, that he wrote on September 3, 1942 to Dr. Frank Kingdon, head of a group called Progressive Citizens of America. This extraordinary letter, in effect a devastating criticism of wartime U.S. foreign policy, was difficult for him to write since he was grateful to the U.S. for having provided refuge and protection in the country that was his home when he did not return to Germany after Adolf Hitler took power in 1933.

In 1905 as a young patent clerk in Bern, Switzerland, Einstein in what is one of the most remarkable and greatest contributions to intellectual history and to science, published four scientific papers. With their presentation in 1915 to the world in four lectures on space, time, and matter, the theories and brilliant insights of Albert Einstein changed the study of physics and the way people view the world.

Though few of us can fully understand Einstein’s special and general theories of relativity, all can appreciate or are aware of him as a genius, the crucial figure in modern physics whose formula E=mc2 is worn on t-shirts at rock concerts.

Einstein was the prolific publisher of more than 300 scholarly papers, but he also published 150 non-scientific ones. He was a social activist, outspoken on many issues not directly related to theoretical physics or mathematics.

In his early days in Princeton, Einstein wrote that in his small town “the chaotic voices of human strife barely penetrate.” By his own actions Einstein proved the opposite was true. He directly influenced world history by signing on August 2, 1939, the letter that was written by fellow physicist Leo Szilard, to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning that Nazi Germany might develop an atomic bomb. Einstein’s argument, that experiments on uranium might develop a new source of energy, leading to a nuclear chain reaction, and the construction of a bomb, was heeded by the president. The experimental work on the problem was speeded up, as Einstein suggested, and the Manhattan Project was established. Ironically, Einstein was not able to work on it, probably because he was regarded as a security risk.

After World War II, Einstein, while still at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, working on unified field theory and quantum physics, was involved in, or was affiliated with, or was a sponsor or honorary chair of more than forty organizations, ranging alphabetically from Ambijan (American Committee for the Resettlement of Jews in Birobijan) to the U.S.-Soviet Friendship Congress. His primary concern was the need for international control of atomic energy and all weapons of mass destruction for which he called in an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of September 1947.

Already in May 1946. Einstein, together with a group of scientists associated with the production of the atomic bomb, set up the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists to advance peacetime uses of atomic energy. As a corollary, he warned in the Bulletin in August 1947, of the danger of military control of U.S. institutions, and argued that the military should not be the agency to distribute funds to institutions for learning and research. He was very concerned about the danger of nuclear weapons and called for their abolition. He opposed the arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union that he said had assumed “hysterical proportions.”

Much of this activity meant association with leftist or liberal causes and organizations. Early on he was a strong opponent of any form of racism and was active in the field of civil rights as a member of the NAACP in Princeton and of the American Crusade to End Lynching. He was a friend of W.E.B Du Bois, Paul Robeson and of the opera diva Marian Anderson. In 1937 he hosted her in his home when she was refused accommodation in the Nassau Inn in Princeton.

Among the many organizations with which he was aligned to some degree were the American-Soviet Friendship movement; the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee of February 1948 (along with Rita Hayworth and Irene Jolliot-Curie); the National Council of the Arts, Scientists and Professions; the National Council of American-Soviet friendship. Sadly, a number of these groups were Communist fronts and were anxious to use the name and prestige of Einstein, who was never a Communist himself.

Among political issues, he supported the Progressive Party of Henry Wallace whom he endorsed as a candidate for president in 1948. Einstein explained that Wallace, whom he invited to his home in Princeton, was “a man who can save us in the threatening internal and foreign policy situation.” He was a sponsor of the Committee of One Thousand that sought the abolition of the House Un-American Activities Committee which was investigating a number of Hollywood personalities. He sponsored and attended, along with Thomas Mann and many other fellow haters of Nazism, the Science and Cultural Conference for World Peace held in New York in March 1949.

Einstein was concerned with Jewish affairs, though he regarded himself as an agnostic and a believer in a “pantheistic” God. He endorsed the activity of the American Birobidjan Committee interested in the settlement of Soviet Jews in Siberia. He thanked the French government on August 11, 1947 for taking measures to prevent the epidemic of measles among Jewish refugee children aboard three British transports off the coast of France.

As a Labor Zionist, in essence a cultural rather than political Zionist, he approved Jewish settlement in the Palestinian area in the 1920s, and always also spoke of the need for a modus vivendi and peace between Jews and the Arab people. He helped set up the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He was offered and declined the position of President of the State of Israel in 1952. He was honorary chair of the American Committee of Jewish Writers, Artists, and Scientists along with the writer Sholem Asch.

In the September 1942 letter, now to be auctioned, Einstein wrote of the new crimes (undefined) committed by the Nazis in France and the assistance given the Nazis by “Vichy traitors.”

Einstein was hesitant about approaching Washington on the matter, because he did not believe in the effectiveness of a “lame and half-hearted lip service brought about by pressure from the outside.” Einstein was very critical of the U.S. government, its failure to help loyalist republican Spain, its flirtation with Fascist Spain, the fact it had an official representative in Vichy France, its failure to assist Russia then in dire need, even its treatment of Finland. He did not believe the official explanations of these policies.

In what seems an anticipation of and resembles but goes beyond some of the rhetoric in the current presidential campaign, Einstein explained U.S. political behavior by the fact that it was controlled to a large degree by financiers whose mentality was similar to the fascist frame of mind. If Hitler were not a lunatic he could have avoided the hostility of the Western powers.

Yet, in spite of this sharp appraisal of U.S. policy, Einstein felt he could not participate in the enterprise that Frank Kingdon was proposing. He was more impressed by deeds and facts than by words. He praised Dr. Kingdon but showed by his own deeds his indefatigable efforts in what he called “the service of humanity and justice.” His 1942 letter makes one wonder which presidential candidate he would support today.