Wisconsin voters ban private money, nonprofits from the election process after 2020 ‘Zuckerbucks’ controversy; spotlight now on 22 states that still allow it.

By Steven Kovac

During the pandemic-plagued 2020 election season, hundreds of millions of dollars from private sources were granted to big cities, an action that many Republicans believe unfairly tipped the scales in favor of Democrats.

Distributed for the stated purpose of protecting public health and assisting people to vote safely, the private funds helped popularize mail-in voting, ballot drop boxes, and ballot harvesting at a scale never seen before.

In the years since 2020, either by legislation or referendum, Republicans have outlawed such private funding in 28 states.

Twenty-two states still allow the practice, raising concerns among Republicans about the integrity of future elections.

“The people of the remaining states should be angry at their legislatures for not banning private money to fund their elections. No government officials should be accepting private payments to do their jobs,” Hans von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation and former member of the Federal Election Commission, told The Epoch Times.

“When you allow private entities to give large donations for local election administration, the money can be used to manipulate the practices of local election officials for political advantage.”

Mr. von Spakovsky said many nonprofits are, in reality, political advocacy groups that have no limit on what they can donate and little reporting accountability.

“They receive unlimited sums of charitable, tax-deductible contributions and then grant them to localities. which has turned out to be a way to move the get-out-the-vote campaign of political parties or candidates into government offices. It’s wrong to use government officials to do that,” he said.

Former Michigan state senator and election integrity activist Patrick Colbeck, a Republican, told The Epoch Times that he believes a larger scheme to privatize the execution of America’s election system is well underway and pointed out another of its perils.

“Nongovernmental organizations are not subject to Freedom of Information requests. They are thus able to operate behind an effective veil of secrecy on what should be the most transparent process in government of them all—our elections,” he said.

Parker Thayer, an investigative researcher with think tank Capital Research Center, said allowing half the country to use private funding in elections is “a national security risk.”

“A 501(c)(3) organization can accept money from anywhere, including foreign sources like Russian oligarchs. Imagine such money being funneled to targeted jurisdictions in Alaska that are about to decide an oil-related referendum,” he told The Epoch Times.

“Since 2020, the hide-the-ball approach of a few big nonprofits regarding where their money comes from has inspired many copycats. It’s only a matter of time before the next copycat does not have America’s best interest at heart. That’s something that all Americans should be worried about.”

Mr. Thayer said the injection of nonprofits into the 2020 system exposed a flaw in the system, reduced trust, and made the running of elections much more partisan.

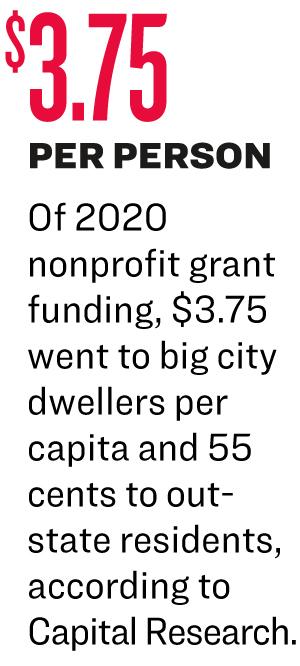

In Wisconsin, 90 percent of 2020 nonprofit grant funding was given to the state’s largest cities; areas that turned out heavily for Joe Biden. Per capita, $3.75 went to big city dwellers and 55 cents to out-state residents, according to Capital Research.

After 2020, Wisconsin legislators twice passed bills to prohibit private money in elections. Twice, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, vetoed the bills.

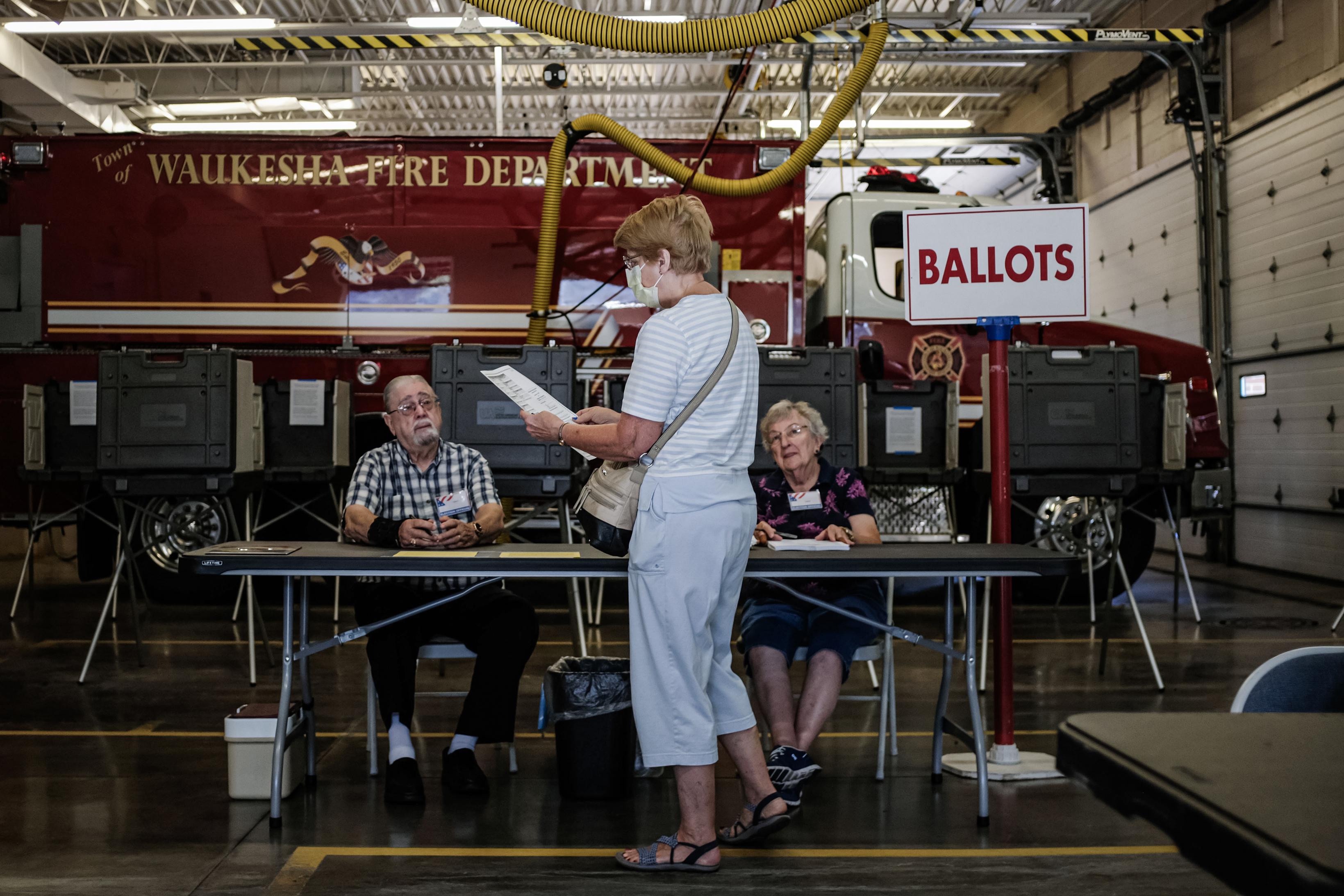

On April 2, primary election voters in the state approved two veto-proof constitutional amendments that stops private money in elections and prohibits privately funded staff from helping run state elections. The amendments passed with 54 percent and 58 percent approval, respectively.

“Wisconsin has spoken, and the message is clear … Wisconsinites have turned the page on Zuckerbucks and secured our elections from dark money donors,” state GOP chairman Brian Schimming said in a statement following the referendum.

Opponents of the amendments stated that the vaguely-worded ban on private funding of elections would create confusion, deprive clerks of badly needed dollars required to conduct elections, and will result in a scaling back of voter outreach programs designed to boost participation.

Before the passage of the Help America Vote Act in 2002, local officials never received federal funding to pay for federal elections.

“They got along just fine for all those years. What has happened in our states and localities?” Mr. von Spakovsky said.

“Local election officials should talk to their legislators rather than going to private donors for money to run their elections.”

Highlighting the partisan divide on the issue, Wisconsin Democratic Party chairman Ben Wikler said in a statement before the referendum, “Rather than work to make sure our clerks have the resources they need to run elections, Republicans are pushing a nonsense amendment to satisfy Donald Trump.”

The former president made a campaign stop in Green Bay on the day of the primary. He was a strong proponent of the two amendments and urged his supporters to get out and vote.

Public ire against the use of private funding in Wisconsin was first stirred in the summer of 2021 when former Brown County Clerk Sandy Juno, a Republican, came forward with allegations that out-of-state political operatives funded by donations from the nonprofit Center for Tech and Civic Life (CTCL) took control of much of the administration of the November 2020 presidential election in Green Bay and other large cities in Wisconsin.

CTCL and another nonprofit organization called the Center for Election Innovation and Research (CEIR) were gifted a total of $420 million by billionaires Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan.

The money, which has since been labeled “Zuckerbucks” by critics, was ostensibly granted to local election offices throughout the United States to purchase personal protection equipment and pay for other means to help local jurisdictions conduct safe and healthy elections during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a post-election accounting, Green Bay reported spending only 0.8 percent of its $1 million “Zuckerbucks” grant on personal protection equipment.

More Abuses Come to Light

Ms. Juno’s allegations were corroborated by special counsel Michael Gableman, a former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice, who was commissioned by the state legislature in 2021 to investigate possible violations of the law and other irregularities in the conduct of the November 2020 election.

The Office of Special Counsel released its report on March 1, 2022. It found that representatives of private organizations participated in much of the planning and administration of the November 2020 presidential election.

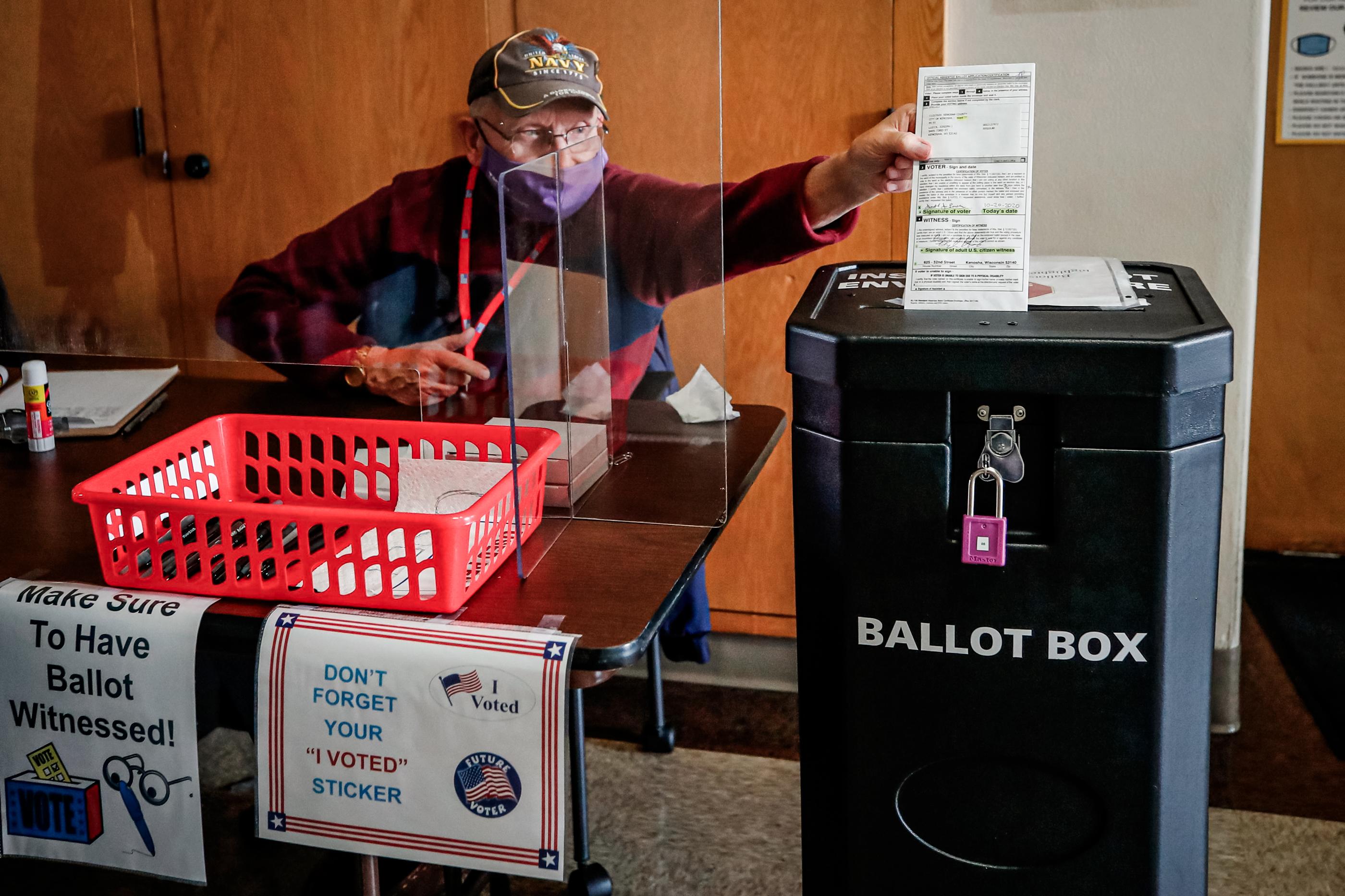

CTCL and other private workers known as “grant mentors,” worked for weeks assisting city election officials and county clerks in writing the instructions controlling the activities of count observers, curing defective mail-in ballots, challenging voters’ ballots, verifying photo ID, setting up voting equipment and vote-counting centers, and training volunteers.

Workers provided by private organizations assigned inspectors for polling places and vote-counting centers, transported ballots to city hall and counting centers, issued a purchase order, made decisions about whether to accept ballots after the closing of the polls at 8 p.m. on Election Day, participated in the counting of ballots, and set up digital networks in polling places, clerks’ offices, and in other buildings, according to the report.

Mr. Gableman wrote that he feared that local election officials, made beholden to private organizations by grant funding, were susceptible to pernicious influence pressuring them to take actions in violation of their oath of office.

Mr. Gableman’s findings further soured many Wisconsinites on the concept of private funds helping to pay for public elections.

Similar problems as those that transpired in Wisconsin in the 2020 election were experienced to varying degrees in other states, many of which enacted reforms.

Democrat Strongholds Benefited Most

Wisconsin communities received $8.8 million in CTCL grant funding that was divided between 216 election offices, with the bulk of the money going to the Badger State’s five largest cities: Milwaukee, Madison, Green Bay, Racine, and Kenosha. This was the pattern across the nation.

The special counsel report found that the Big Five cities received $6.3 million of the CTCL grant money. All the grants were conditioned on the individual locality agreeing to the grant’s mission statement known as the Wisconsin Safe Voting Plan.

The plan was drawn up by city officials and submitted to CTCL as a prerequisite to receiving the grant funding.

One of the recommendations of the Safe Voting Plan was to “Dramatically expand strategic voter education and outreach efforts, particularly to historically disenfranchised residents.”

The plan said Wisconsin election officials had learned that, because of the pandemic-induced confusion exhibited by voters in the April 2020 primary election, they required “considerable public outreach and individual hand-holding to ensure their right to vote.”

In his report, special counsel Gableman, a Republican, alleged that the Safe Voting Plan was little more than a partisan campaign program designed to maximize voter registration and turnout in heavily minority-populated precincts.

He noted that the Wisconsin Election Commission, the bipartisan state oversight authority, supported the Safe Voting Plan get-out-the-vote program.

Mr. Gableman said the Big Five cities spent grant money on voter education, a multimedia advertising campaign, and a phone blitz, among other things. They employed geo-fencing to pinpoint particular areas of geographic and demographic interest.

The cities also used the grant money to pay for personnel called “voter navigators” (also known as ballot harvesters) to shepherd prospective voters through the absentee voting process—a practice later declared unlawful by the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

The municipalities also purchased and installed unstaffed absentee ballot drop boxes in strategic locations, which was also struck down as illegal by the state’s highest court.

The grant-funded public relations campaigns in each city zeroed in on preferred racial groups, which, according to the OSC report, coincidentally matched the demographic profile of Biden voters.

CTCL has stated that neither Mr. Zuckerberg or Ms. Chan had any input into which communities received the grants, and that the organization’s nonprofit tax-exempt status prohibited it from engaging in partisan politics. Mr. Zuckerberg called the 2020 grant program “a one-time” effort.

In 2020, CTCL grants went to 2,500 election offices spread over 49 states. The grants ranged from a minimum of $5,000 to a maximum award of $19 million, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Across the nation, the largest cities received the lion’s share of grant money. For example, the Democrat stronghold of Milwaukee received $3.4 million in CTCL grant funds in 2020.

Democrats OK With Private Funds

Republicans contend that the programs funded by Zuckerbucks, with the attendant abuses described above, may have made the difference in the 2020 election.

Mr. Trump narrowly won Wisconsin in 2016 but lost the state to Joe Biden by just under 21,000 votes (0.63 percent) in 2020.

In the battleground state of Michigan, which Mr. Trump won in 2016 and lost in 2020, voters approved a constitutional amendment in 2022 that guarantees the right of local governments to accept and spend publicly disclosed private monetary donations and in-kind contributions to run elections. The Great Lakes State also now mandates the use of absentee ballot drop boxes in every election jurisdiction.

Five Democrat governors have vetoed legislation banning private funding of elections: Louisiana, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

The Republican-dominated legislature in North Carolina overrode Democrat Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto.

As of April 3, private money paying for elections has been curtailed or banned in five of the seven recognized battleground states. Going into November, bans are on the books in Wisconsin, North Carolina, Georgia, Arizona, and Pennsylvania. Private funding of elections is legal in Michigan and Nevada.

Democrat-dominated legislatures in deep blue states have shown zero interest in eliminating the practice.

Of the 28 states that have either totally banned or restricted the use of private donations in election administration, most have made exceptions for food and drink and the use of a building for a polling location.

State Laws Vary

Ohio passed comprehensive legislation in 2021 that prohibits election officials from collaborating with or accepting or expending any money from a non-governmental source on elections, according to a report by the National Council of State Legislatures.

The Ohio law, regarded by some as a model for the nation, explicitly forbids private funding of voter registration, voter education, voter identification, get-out-the-vote activities, absentee voting, and election official recruitment or training.

Virginia has outlawed the use of private funds for voter education. outreach, and voter registration programs since 2022.

Florida’s ban passed in 2021 adds the cost of litigation related to election administration to its list of prohibited uses.

The ban in Idaho allows private donations of a value of $100 or less.

Foreign governments are included in the list of donors banned by Louisiana.

The 2022 Mississippi law that bans private contributions to the running of elections exempts individuals who, without compensation, give of their personal time to assist in voter education, voter outreach, voter registration programs, or other election-related activities.

Recognizing its underfunding of the conduct of elections, the state of Missouri provides that “In every even-numbered year in which the amount of state funds appropriated to proportionately compensate counties…is less than the amount of such funds that were appropriated in the previous even-numbered year, private money may be received by the secretary of state to disburse to counties based on the amount of registered voters in each county.”

In Montana, all costs and expenses relating to elections must be paid for with public funds. However, the ban exempts tribal nations, who are allowed to use their own funds or the funds of other tribal nations or money from the state and federal government to pay for elections.

As of Jan. 1, North Carolina expressly prohibits the State Board of Elections from accepting private contributions to employ individuals on a temporary basis to work on elections.

Nonmonetary private donations to election jurisdictions are allowed by North Dakota unless they would be used to prepare, process, mark, collect or tabulate ballots or votes.

Written approval by the governor and notification of the speaker of the house and president pro tempore of the senate are required before a private donation for election administration can be made in Oklahoma. Similar oversight requirements are in effect in Tennessee, West Virginia, and Texas.

The key swing state of Pennsylvania banned private funding of voter registration, and the preparation, administration and conducting of an election. Donation of a polling location, contributions of uncompensated labor by volunteers and the donation of goods valued less than $100 are exempted.

Political analysts have noted that the ban on private funding for elections in more than half of the states has deprived Democrats of a tool that worked very effectively to their advantage in 2020.

A New Alliance

In 2022, CTCL led the way in forming the U.S. Alliance for Election Excellence, a coalition of nonprofit organizations and election officials dedicated to an $80 million, five-year program to “envision, support, and celebrate excellence in U.S. election administration,” according to its website.

The group intends to establish Centers for Election Excellence in selected localities across America and bring election offices into its program.

“We’ll begin with the election office’s unique challenges and goals, then provide them with customized resources, coaching, and implementation support,” the website states.

In its Q&A section of its website, the Alliance asks: “What if an election office receives backlash by participating in this program?”

It answers by stating, “Election officials deserve a warm, welcoming community of support where their hard work is encouraged and celebrated. The Centers will receive guidance and resources to help tell their story, combat misleading information, and keep their teams safe.”

Madison, Wisconsin; Clark County, Nevada; and North Carolina’s Brunswick and Forsyth counties were among the first beneficiaries.

“These jurisdictions are committed to safe, secure, and inclusive elections that put voters first,” said CTCL’s executive director Tiana Epps-Johnson in announcing the selections.