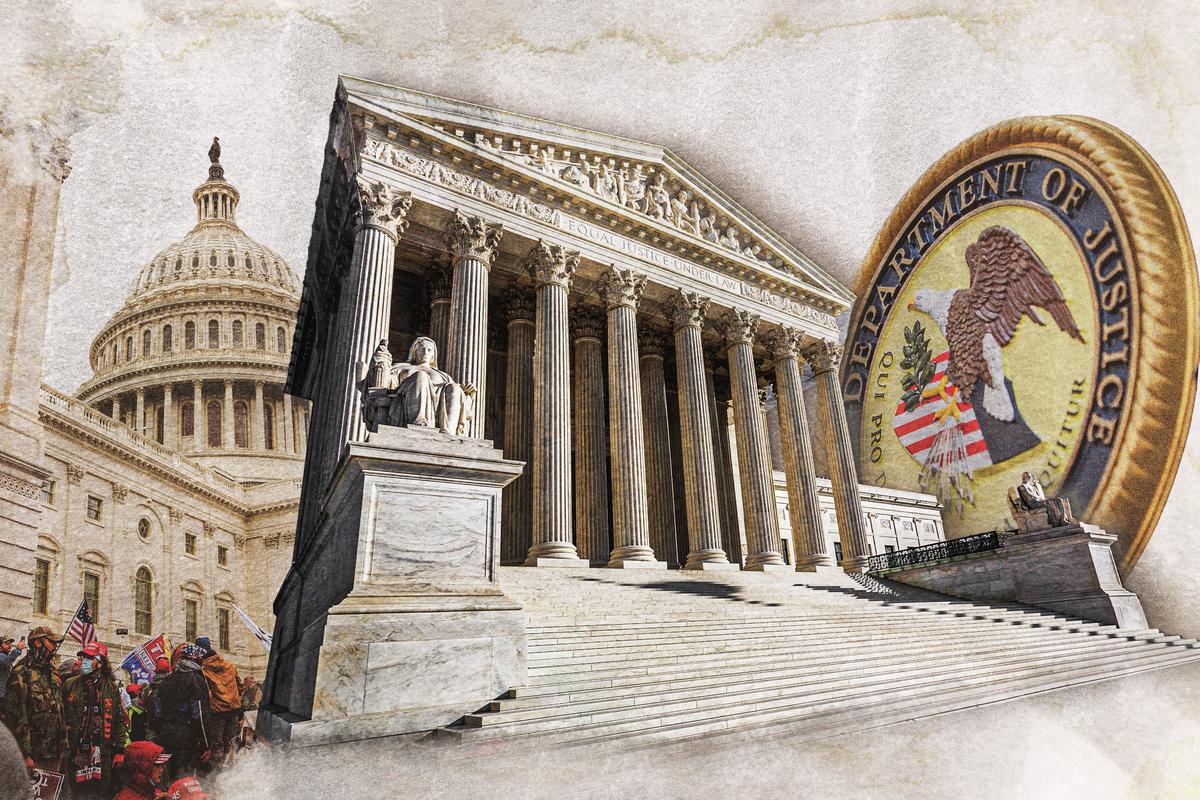

The decision will affect more than 330 defendants and could eliminate the DOJ’s unprecedented and novel use of a law designed for white-collar crime.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to take up a Jan. 6 case that challenges the most frequently charged felony from that day could upend more than 330 criminal cases and eliminate the most potent weapon wielded by the Department of Justice (DOJ).

On Dec. 13, the High Court granted certiorari to a petition of appeal from Jan. 6 defendant Joseph W. Fischer, 57, of Jonestown, Pennsylvania.

Mr. Fischer is among the hundreds of defendants in cases regarding the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol breach who are charged with corruptly obstructing an “official proceeding”—the joint session of Congress that met to tally Electoral College votes and hear objections from members.

The DOJ put the Jan. 6 protesters in its sights with the unprecedented use of a 2002 evidence-tampering statute to prosecute them for delaying the counting of votes from the 2020 presidential election.

The Supreme Court’s decision could knock the heart out of hundreds of prosecutions and quash the unorthodox use of a law not designed to apply to anything but corrupt accounting practices.

18 U.S. Code Section 1512(c) reads:

Whoever corruptly (1) alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding; or (2) otherwise obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding or attempts to do so, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

The charge has been levied in federal court against high-profile Jan. 6 defendants—including former President Donald Trump, Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes III, former Proud Boys chairman Henry “Enrique” Tarrio—and hundreds of lesser-known figures.

Even defendants who came to the U.S. Capitol well after Congress was evacuated on Jan. 6 were charged with obstruction of an official proceeding. A number argued unsuccessfully at trial that they couldn’t have obstructed Congress because they weren’t present in the Capitol when lawmakers left the House and Senate chambers.

Mr. Fischer was indicted in March 2021 on charges of obstruction of an official proceeding; civil disorder; assaulting, resisting, or impeding certain officers; entering and remaining in a restricted building or grounds; disorderly and disruptive conduct in a restricted building or grounds; disorderly conduct; and parading, demonstrating, or picketing in a Capitol building. He pleaded not guilty to all charges.

Pressure for Plea Deals

Defense attorneys have said the maximum 20-year prison term that comes with a violation of 18 U.S. Code Section 1512(c)(2) puts tremendous pressure on defendants to take a DOJ plea offer rather than go to trial.

Eleven of 12 district judges in the District of Columbia federal court have upheld the DOJ’s use of Section 1512, while U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols has thrown out the charge in seven Jan. 6 cases.

Critics say prosecutors’ use of Section 1512 has weaponized a statute that was never intended to address political protests or First Amendment activities. One legal researcher called it “dangerous.”

“If the Biden DOJ’s adventurism is allowed to stand, it will permanently change the ability of the government to suppress the rights of American citizens,” Jonathon Moseley told The Epoch Times. “Every American will be at the whim of any prosecutor to terrorize them.”

Mr. Moseley said that if the Supreme Court strikes down the use of Section 1512 in such a manner, it could lead to new trials.

“If the attorney files a Rule 33 motion for a new trial based on this new information, they’d probably get it, and they probably get a new trial without that count,” Mr. Moseley said. “I think it would be better just to dismiss it entirely.”

In its reply brief, the DOJ criticized the defendants’ “cramped, document-focused interpretation” of Section 1512, arguing for a more expansive reading of the term “otherwise.”

“Accordingly, giving the statute its ‘natural’ reading, Section 1512(c)(2) prohibits corruptly obstructing an official proceeding in a different way or manner than the acts of document alteration, destruction, and concealment targeted in Section 1512(c)(1),” U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar wrote.

‘Huge Humiliation’

Defense attorney William Shipley, who worked as a federal prosecutor for 22 years, said that if the Supreme Court strikes down the use of Section 1512, it will be a major blow to the DOJ—and “draw adverse scrutiny” to the majority of D.C. district judges.

“It’s going to be a huge, huge humiliation for the Department of Justice, which has run crazy with this interpretation,” Mr. Shipley told The Epoch Times. “Because they’ve never used the statute in this same way before. This is a novel use, even by DOJ [standards], of this particular statute.

“This would be a humiliation of the entire management of the department that is behind the use of the statute.”

The DOJ has taken misdemeanor trespassing and property damage cases and turned them into 20-year felonies by using Section 1512(c)(2), Mr. Shipley said.

“And so it’s just a hammer that they have been able to bludgeon people into pleading guilty with to avoid the consequences of going to trial and [possibly] losing. And oh, by the way, they’ve won every trial, which they knew they would,” he said.

Retired Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz said most of the protests at the Capitol were protected First Amendment demonstrations.

“Look, these were not obstructions of justice,” Mr. Dershowitz told Newsmax on Dec. 15. “These were attempts to exercise First Amendment rights to petition the government for a redress of grievances. Some of the people went too far and destroyed property, but those people who just tried to influence the congressional hearings were exercising their constitutional right.”

Edward Tarpley, a defense attorney who represented Mr. Rhodes in the first Oath Keepers trial in 2022, said the Supreme Court’s decision to hear the appeal is a “tremendous victory.”

“Virtually everyone agrees that this statute was never intended to be used the way the DOJ has used it against the January 6 defendants,” Mr. Tarpley told The Epoch Times.

History of Section 1512(c)(2)

The statute was part of the mammoth Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which aimed to combat corporate fraud and increase accountability in the financial disclosures of publicly traded companies. The legislation was co-authored by Sen. Paul Sarbanes (D-Md.) and Rep. Michael Oxley (R-Ohio).

The Sarbanes-Oxley bill (HR 3763) was approved by the U.S. House in a 423–3 vote and by the Senate 99–0. President George W. Bush signed the act in the East Room of the White House on July 30, 2002.

“No more easy money for corporate criminals, just hard time,” President Bush said at the signing ceremony. “The era of low standards and false profits is over. No board room in America is above or beyond the law.”

Sarbanes-Oxley was driven in part by public outrage over corporate fraud scandals at Enron Corp., WorldCom Inc., Tyco International Ltd., Adelphia Communications Corp., and other firms.

Energy giant Enron used suspect accounting practices in an effort to hide its shrinking profits and inflate the appearance of earnings. The company kept failing assets off the books by transferring them to “special purpose entities” (SPE)—partnerships with outside entities.

The provisions of Section 1512(c) used against the Jan. 6 defendants are contained in a section of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act titled the “Corporate Fraud Accountability Act of 2002.”

After the Securities and Exchange Commission began investigating Enron’s use of SPEs in 2001, some officials at Arthur Andersen LLP began shredding documents connected to Enron’s audits. Arthur Andersen served as Enron’s auditor and as a consultant to the company. Enron’s stock shortly went into free fall. In December 2001, the $60 billion firm filed for bankruptcy court protection.

Defense attorney Joseph McBride said he believes that the DOJ’s novel use of the law is based on “corruption and political hatred.”

“For the love of God, what do the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and election-related protests have to do with each other?” Mr. McBride told The Epoch Times. “I’ll tell you—absolutely nothing.”

Judge Nichols threw out the obstruction charge filed against Mr. Fischer and defendants Edward Jacob Lang, 28, of New York, and Garret A. Miller, 37, of Texas. Mr. Miller and Mr. Lang filed similar petitions of appeal with the Supreme Court, but the justices agreed to take up only the Fischer case.

In a March 2022 memorandum opinion, Judge Nichols said the charge against Mr. Miller “requires that the defendant have taken some action with respect to a document, record, or other object in order to corruptly obstruct, impede or influence an official proceeding.”

“Miller, however, is not alleged to have taken such action,” he said.

Judge Nichols said he was faced with a “serious ambiguity in a criminal statute.” Federal courts have traditionally exercised restraint when evaluating the reach of a statute and applied the rule of lenity to resolve any ambiguity in favor of the defendant, he said.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit muddied the waters in April with a fractured 1–1–1 decision. Only a partial concurrence by one of the judges appeared to reverse Judge Nichols and uphold the DOJ’s broad interpretation of the law.

Among the complicating issues in the case is the lack of a definition for the term “corruptly” and whether the term “otherwise” in Section 1512(c)(2) refers to conduct listed in Section 1512(c)(1)—altering, destroying, mutilating, or concealing a record, document, or other object—or has a much broader meaning.

Judge Nichols said “legislative history supports a narrow reading of subsection (c)(2).”