When President Biden took office, he sent several signals that he was ready to take on increasing corporate concentration. Among the clearest was appointing the consumer advocate Lina Khan — a prominent critic of monopoly power — to lead the Federal Trade Commission.

Editor’s Note: Of course while, at the direction of federal health care agencies and blind obedience of cities and states , Biden was shutting down businesses right and left.

Instead, the takeovers have persisted under Biden’s watch. Last week brought the latest evidence that reducing corporate concentration will be more difficult than Biden might have hoped: U.S. courts rejected the F.T.C.’s attempts to block Microsoft from absorbing the video game company Activision Blizzard. Microsoft could finalize the deal in the coming months; a key deadline was extended this week.

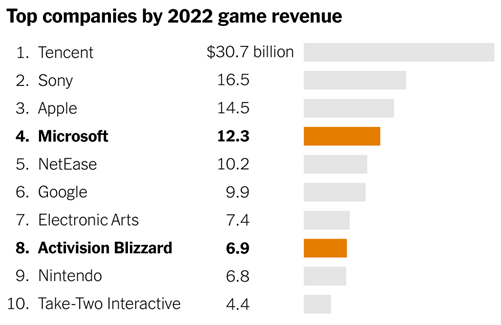

The merger would be by far the biggest ever in video games, after adjusting for inflation. The game industry now accounts for significant chunks of the economy. It is larger than music, U.S. book publishing and North American sports combined. Microsoft’s game division and Activision Blizzard each make more money annually than all U.S. movie theaters. The two companies are among the biggest in games, as this chart by my colleague Ashley Wu shows:

The F.T.C. said that the Microsoft-Activision merger was anticompetitive and sued to stop it. The agency argued that the merger would give Microsoft, maker of the game console Xbox, too big of an advantage over its rival Sony, the maker of PlayStation. Of particular interest was Activision’s massive franchise, Call of Duty. A new edition of Call of Duty is consistently one of the best-selling games on Xbox and PlayStation each year. But if Microsoft owns Call of Duty, it could make the game exclusive to Xbox and rob Sony of one of gaming’s biggest attractions.

To address those concerns, Microsoft promised that it would put Call of Duty games on PlayStations for 10 more years. That was one reason the courts ruled against the F.T.C.: They found the agency had not shown that the deal would likely hurt competition.

With their ruling, the courts are allowing another big merger that will further consolidate a major industry. Many experts say that trend is ultimately hurting consumers by diminishing the kind of competition that lowers prices and improves quality for goods and services, even if the F.T.C. wasn’t able to prove all of that in this case.

Concentrated power

Let’s zoom out. In the past several decades, markets have become more concentrated. The very biggest companies dominate most industries, as this chart shows:

Why does this matter? In simple terms, a lack of competition lets companies lower wages, increase prices and dilute the quality of their products. A classic example is internet service: Many Americans live in places with only one or two providers. These companies keep prices high, the internet can be spotty and the customer service is often bad. Since customers don’t have alternatives, providers can get away with those faults.

Corporate concentration deepens that kind of problem, experts say. One economist concluded that market concentration costs the typical American household more than $5,000 a year. Progressives like Khan have argued that regulators need to take the issue more seriously.

Courts push back

The Biden administration released guidelines this week that seek to toughen antitrust law, which restricts anticompetitive practices. Under Khan, the F.T.C. has also pushed courts to effectively lower the burden of proof required to show that a merger is anticompetitive. There is merit to that approach, some experts argue: U.S. courts have raised the bar very high over the past few decades, surpassing standards in the U.K. and much of Europe.

“We can convict someone and send him to prison for murder on the basis of circumstantial evidence,” said Douglas Melamed, an expert on antitrust issues at Stanford Law School. “But it often seems that courts will not let plaintiffs win an antitrust case based on circumstantial evidence.”

The F.T.C. has yet to persuade the courts to ease their standards. The agency’s loss in the Microsoft-Activision case is the latest example. It also failed to block Meta’s acquisition of a virtual reality firm, Within. And it has even lost in its own administrative court, which ruled in favor of the gene-sequencing company Illumina in its acquisition of the firm Grail.

Khan’s cause still has potential. The last major shift in antitrust law, in the 1970s, came after decades of work by conservatives to push the law and courts in their direction. The movement that Khan helped popularize among progressives is only a few years old. If it persuades more of the public and, most importantly, judges, it could eventually succeed.

New York Times