In the long corridor of forgotten champions of liberty, few names deserve to be dusted off and remembered more than Paul de Rapin — a French Protestant, a political exile, a soldier turned historian. Rapin’s life was not merely a series of odd turns. It was a pilgrimage toward truth, a life spent illuminating the principles of constitutional government. Though he died nearly three decades before the Declaration of Independence was signed, his fingerprints can be found all over the parchment and the minds of the men who signed it.

Background

Born in 1661 in Castres, France, Paul de Rapin came of age during a time when the sword of state was aimed squarely at the heart of religious dissenters. As a Huguenot, Rapin watched his fellow Protestants hounded, harassed, and hanged by Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The so-called Sun King cast a long shadow, but Rapin would not grovel. He fled his homeland for England, where liberty of conscience was still something worth dying for — and worth living for, too.

Rapin served briefly in the army of William III, but his mind, not his musket, would become his greatest weapon. Exchanging the battlefield for the library, he embarked on a task few others dared. He wrote a history of England that was honest, comprehensive, and animated by the cause of constitutional liberty. His History of England, published in French between 1724 and 1727 and later translated into English, was an instant classic — not for its style, but for its substance. Rapin wasn’t writing bedtime stories for courtiers. He was constructing a monument to the English constitution.

What made Rapin’s work revolutionary wasn’t just his recounting of kings and parliaments. It was his central thesis: that the liberty of the English people was a birthright, secured through centuries of struggle — from Magna Carta to the Glorious Revolution. He wasn’t merely chronicling events. He was interpreting them as a tapestry of resistance to tyranny, woven by the hands of barons, bishops, and commoners alike.

Influence on the Founding Fathers

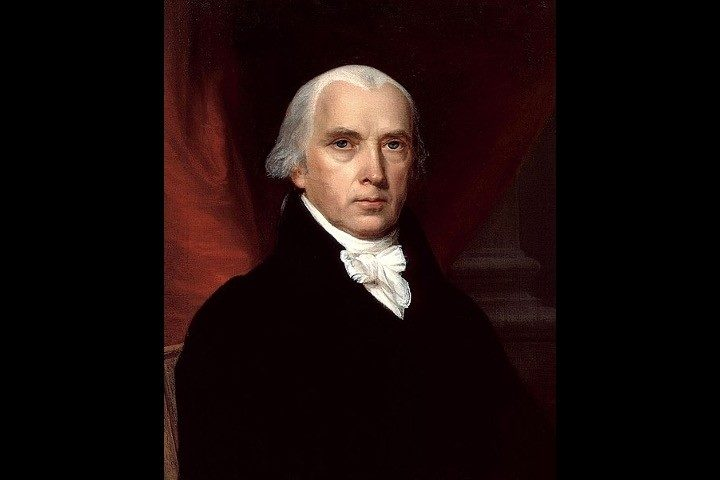

Paul de Rapin died in 1725, but his ideas lived on — and not just in Britain. Across the Atlantic, a generation of American colonists cut their political teeth on Rapin’s pages. Thomas Jefferson owned multiple editions of his work. John Adams cited Rapin often in his own political essays. Even James Madison — the so-called “Father of the Constitution” — absorbed from Rapin the understanding that liberty is preserved not by parchment, but by perpetual vigilance against power.

It was Rapin who gave the American founders the language of liberty rooted in history. He taught them that freedom was not a French invention or a British indulgence. It was a principle older than any crown, validated by the blood of patriots across generations. His chronicles revealed a constitutional tradition stretching back 500 years — a tradition that could not be reconciled with the political plundering of George III and his Parliament.

In many ways, Rapin provided the philosophical bridge between the English Whigs and the American revolutionaries. He was the lantern-bearer, lighting the path from Runnymede to Philadelphia. His works were not dry tomes of dusty dates. They were firebrands, smuggled across oceans and time, igniting the hearts of men who would rather die free than live as subjects.

A Legacy Worth Reviving

Today, few students of American history are taught the name Paul de Rapin, and that is a shame. His life reminds us that ideas are weapons, and that exile is no excuse for silence. Rapin didn’t just study liberty; he suffered for it. He wrote not from comfort, but from conviction. And the world he helped shape — a world where governments are held in check by the people, not the other way around — still stands because men like him stood first.

Let us remember him not as a footnote, but as a forefather of freedom. Let us read his works, quote his words, and, most importantly, follow his example. For in the face of rising tyranny, Rapin would tell us what he told his generation: The history of liberty is not finished. And neither is the fight.

Quotable Quotes From Paul de Rapin:

“Our strength often increases in proportion to the obstacles imposed upon it.”

“So true it is, the greatest events spring sometimes from things that appear at first of very little consequence.”

“The mutual animosity of the two parties was so violent, civil war, that they soon came to blows, each preferring his private; to the public interest.”

“History represents to us four things, which are essential to it: 1. The events; 2. The place where they happened; 3. The time when they happened; 4. The persons who were the actors.”

“In order to understand a history perfectly, it is necessary to have a knowledge of the country where the scene of the action lies, by means of geography, and of the times wherein they were transacted by chronology; it is no less requisite to know the persons concerned, by the help of genealogies, which very often discover the motives and reasons of things.”