Eminent domain is becoming the weapon of choice against opposition to large wind and solar projects being planned and constructed around the United States.

The dream of net-zero carbon emissions—and its vision of blanketing hundreds of millions of acres of American land with wind turbines and solar panels—is running up against the reality that most of the land in America is still privately owned and many Americans don’t want these massive industrial installations near their homes.

But that may prove to be a temporary impediment.

“There is a major effort under the Biden administration to consolidate power over land and resources, because whoever owns the land and resources of a nation, controls the people,” Margaret Byfield, executive director of American Stewards of Liberty, a property rights nonprofit, told The Epoch Times.

As a former Nevada rancher, she became embroiled in a decade-long fight with federal agencies over control of her land, which she ultimately lost.

Today, she sees another land grab coming in the form of the Green New Deal and the renewable energy industry.

Analysts speculate that in order to meet net-zero goals and build out a renewable energy infrastructure, enormous swaths of land will have to be converted for industrial use.

Bigger Than Texas

“With current siting practices, an area the size of Texas is required to accommodate the wind and solar infrastructure we need to reach nationwide net-zero emissions by 2050,” said Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist of The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a renewable energy advocate.

Reaching the goal of net-zero carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2050 would require consuming more than 250,000 square miles, or 160 million acres, of land, according to TNC’s May report.

However, the authors are optimistic that land consumption could be reduced to an area the size of Arizona if the renewable industry follows TNC’s “impact reduction” procedures.

These grand schemes are being held up by the fact that 70 percent, or 1.3 billion acres, of the land in the contiguous 48 states is currently privately owned, and its owners often refuse to allow solar panels, wind turbines, power lines, and carbon pipelines to be installed.

According to the Renewable Rejection Database, compiled by journalist and author Robert Bryce, more than 600 communities across the United States have so far blocked or banned large solar and wind projects and other renewable energy ventures that they believe will damage local environments.

“It’s about property values, it’s about maintaining the character of their neighborhoods in their towns, in their counties,” Mr. Bryce told The Epoch Times. “And this is something that has been happening from Maine to Hawaii.”

Eminent Domain

For the net-zero industry, however, centralizing land rights may solve this problem.

A 2020 report by Vanderbilt Law School faculty J.B. Ruhl and James Salzman states that “the multi-faceted infrastructure goals of the Green New Deal will be impossible to achieve in the desired timeframes if the existing federal, state, and local siting and environmental protection statutory regimes are applied.”

“Business, labor, property rights, environmental protection, and social justice interests will use them to grind the Green New Deal to a snail’s pace,” the report reads.

“This Essay is a call to arms for the need to design New Green Laws for the Green New Deal.”

The authors advocate for “more streamlined, top-down, preemptive processes, as well as extensive use of eminent domain powers” to speed the development of wind and solar projects.

In line with this view, Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., America’s largest bank, said in an April letter to shareholders that governments, corporations, and nongovernmental organizations must unite behind a “massive global investment in clean energy technologies.”

“We may even need to evoke eminent domain,” he wrote.

This belief is resonating with government officials, both at the federal level and also within left-leaning states.

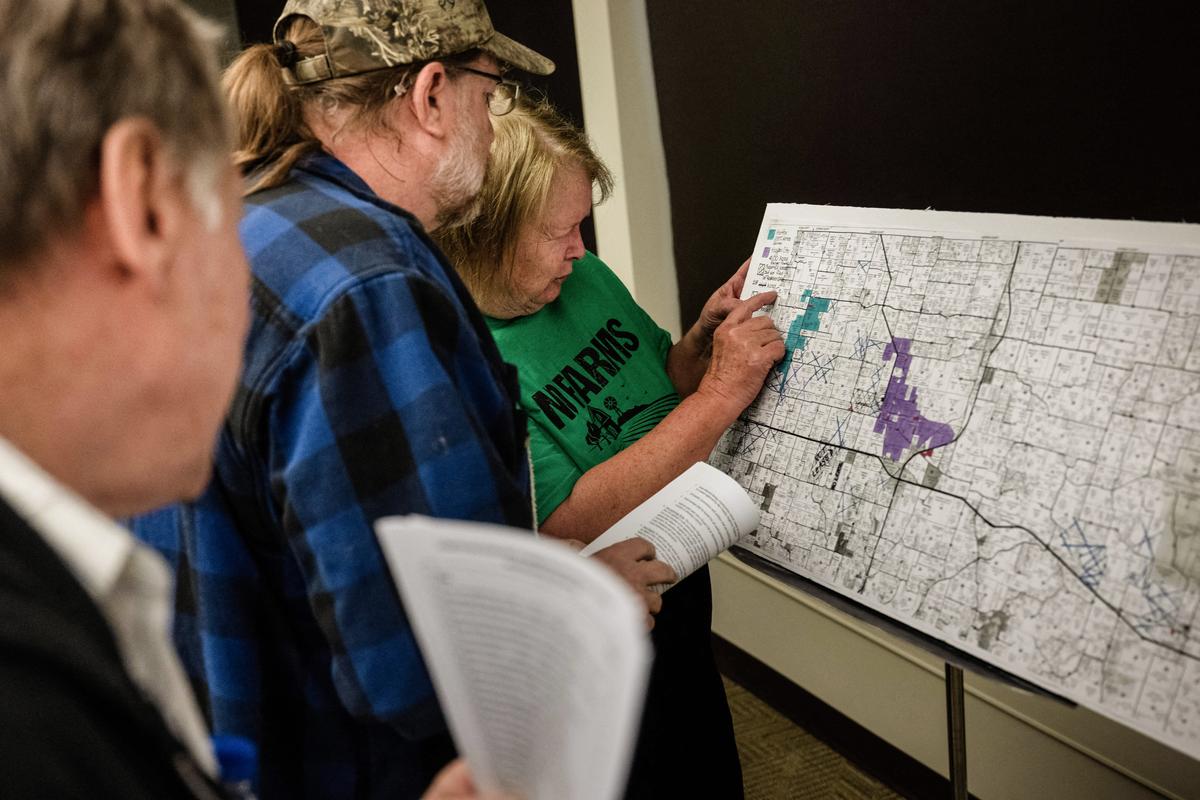

In November, the Democrat-controlled Michigan Legislature passed a law that aims to take the control of land use from local communities and give it to state officials for renewable energy projects.

According to Michigan’s new law, permits for solar farms with a capacity of 50 megawatts or more; wind facilities with 100 megawatts or more; and energy storage facilities with a capacity of 50 megawatts or more and a discharge capacity of 200 megawatts or more will now be under the control of the Michigan Public Service Commission.

This will remove the impediment of local resistance to large-scale renewable energy projects.

According to a statement from Michigan state Sen. John Damoose, a Republican who opposed the law, those who pushed it “knew communities wouldn’t want to be packed full of wind farms and solar panels, so they had to introduce more bills that give the state the power to overrule local communities.”

More Eminent Domain

In addition to government authority, private companies are also seeking the power to take land in the name of net zero.

A test case is currently playing out in western states over carbon-capture pipeline projects, in which private companies are attempting to take people’s land by eminent domain, insiders say.

Two companies, Summit Carbon Solutions and Navigator CO2 Ventures, have been attempting to construct carbon sequester pipelines through five western states.

Navigator’s carbon capture project, called Heartland Greenway, would capture 15 million tons of CO2 emissions per year from ethanol plants and pipe it off to where it could be buried thousands of feet underground.

Summit’s proposed project is larger, projected to capture 18 million tons of CO2. It would connect to more than 30 ethanol plants in Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, Minnesota, and North Dakota, where the CO2 would ultimately be sequestered.

These companies would have received federal subsidies of $50 per sequestered ton of CO2 under the Trump administration.

Under President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, these subsidies were increased to $85 per ton, in addition to what pipeline owners would receive from the ethanol producers.

“It’s a big boondoggle, and there is a ton of money to be made,” South Dakota state Rep. Karla Lems told The Epoch Times.

“But the real kicker is that they have to do this pipeline through private property.”

The way it has been achieved is by companies declaring themselves “common carriers,” which historically has been a designation for railroads, water companies, and natural gas pipelines.

This designation allows private companies to take privately owned land by eminent domain.

According to Ms. Lems, more than 150 landowners in South Dakota were served papers by Summit condemning portions of their land, thus allowing the company access to it.

“My biggest concern is that we are setting a precedent,” she said. “This is eminent domain for private gain.

“They’re coming in and they’re saying: ‘We need an easement through your property, and you will give it to us, one way or another, because we are a common carrier and we have the right to eminent domain.’”

The companies did try to negotiate with landowners, Ms. Lems said, “but basically, they have that big stick of eminent domain in their back pocket, and they’re not afraid to use it.”

If the pipeline succeeds, “solar and wind are right behind them.”

Navigator, which is 84 percent owned by asset manager behemoth BlackRock, has put its project on hold because of local resistance and reportedly hasn’t made attempts to take land by eminent domain.

But Summit is continuing to push forward with its pipeline plan.

In a letter to South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, 22 state representatives said that “the ‘Green New Deal’ that has been thrust upon South Dakota because of the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals does not fit with our Bill of Rights.”

“The false narrative that says ESG [environmental, social, and governance] scores tied to the ‘net-zero’ carbon score will repair the damage caused by capitalism goes against the very nature of our founders,” the state legislators wrote.

“Companies that stand to benefit from these projects do so at the expense of the property rights of individuals.”

Many lawmakers in state governments support the project, and ethanol producers say they need the carbon credits that the pipeline will give them in order to continue to operate profitably.

But critics of the project question why local industry and landscapes must be reconfigured to meet the global warming goals of the Biden administration and others.

“It’s crazy the amount of political pressure to get this done,” Ms. Lems said.

“Why do we have to go along with the World Economic Forum rules? Let’s form a coalition that says we’re not going to follow those rules; they make no sense.”

Critics of the net-zero agenda point out that all the money being spent and the land being acquired in the name of net zero can’t succeed in reducing global temperatures.

Property Rights and Political Freedom

In addition to the land acquisition for net zero, the Biden administration announced its 30×30 program in a January 2021 executive order. The order states that 30 percent of America’s land and water should be set aside for “conservation” by 2030.

While supporters of this plan have characterized it as “voluntary” and “grassroots,” opponents have deemed it a federal land grab and are concerned that it’ll include new government mandates over private property.

According to Ms. Byfield, America’s founders wanted private ownership of land and property because property rights and political rights go hand in hand.

The East Coast is largely privately owned, but land in the west, which was developed under a different set of beliefs, is about 50 percent federalized,” she said.

“Our founders wanted a separation of power, which meant the people, the citizens, the small landowners, the middle class, would own our natural resources.

“And we’re now moving to the consolidation of power, and the people have the least amount of power.”