The last time the Supreme Court waded this deep into a presidential election was more than two decades ago in Bush v. Gore.

The Supreme Court is set to hear one of the most consequential cases in the nation’s history while considering complex legal questions that could affect the election.

Oral argument will take place on Feb. 8 in Trump v. Anderson, which questions whether the Colorado Supreme Court erred in ruling that a post-Civil War constitutional provision disqualifies former President Donald Trump from appearing on the state’s ballot.

Depending on their ruling, the justices could influence the presidential election in a way not seen since Bush v. Gore in 2000.

In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that Florida’s decision to recount the 2000 presidential election ballots violated former President George W. Bush’s right to equal protection under the 14th Amendment.

Now, that same amendment is before the court but with a new set of justices (besides Justice Clarence Thomas), a provision tested much less in the courts than the equal protection clause, and an untold number of questions about its meaning.

One of the many amicus briefs submitted to the court was authored by several law scholars, including former Ohio Solicitor General Edward Foley. The authors warn that the current case is “more perilous” than the one the court faced in Bush v. Gore.

They worry that if the Supreme Court passes the buck to Congress rather than issuing a decisive opinion, it could lead to political violence.

They speculated that Congress effectively invalidating Americans’ votes could lead to a scenario similar to the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol breach.

“Requiring Congress to take up the issue in an inherently political process, on the fourth anniversary of the U.S. Capitol riot, would be a tailor-made moment for chaos and instability,” the authors wrote.

“The pressure on Congress from all sides would be enormous, as would be the temptation to resolve the disqualification question not as a matter of the legal or factual merit, but as an exercise of political power.”

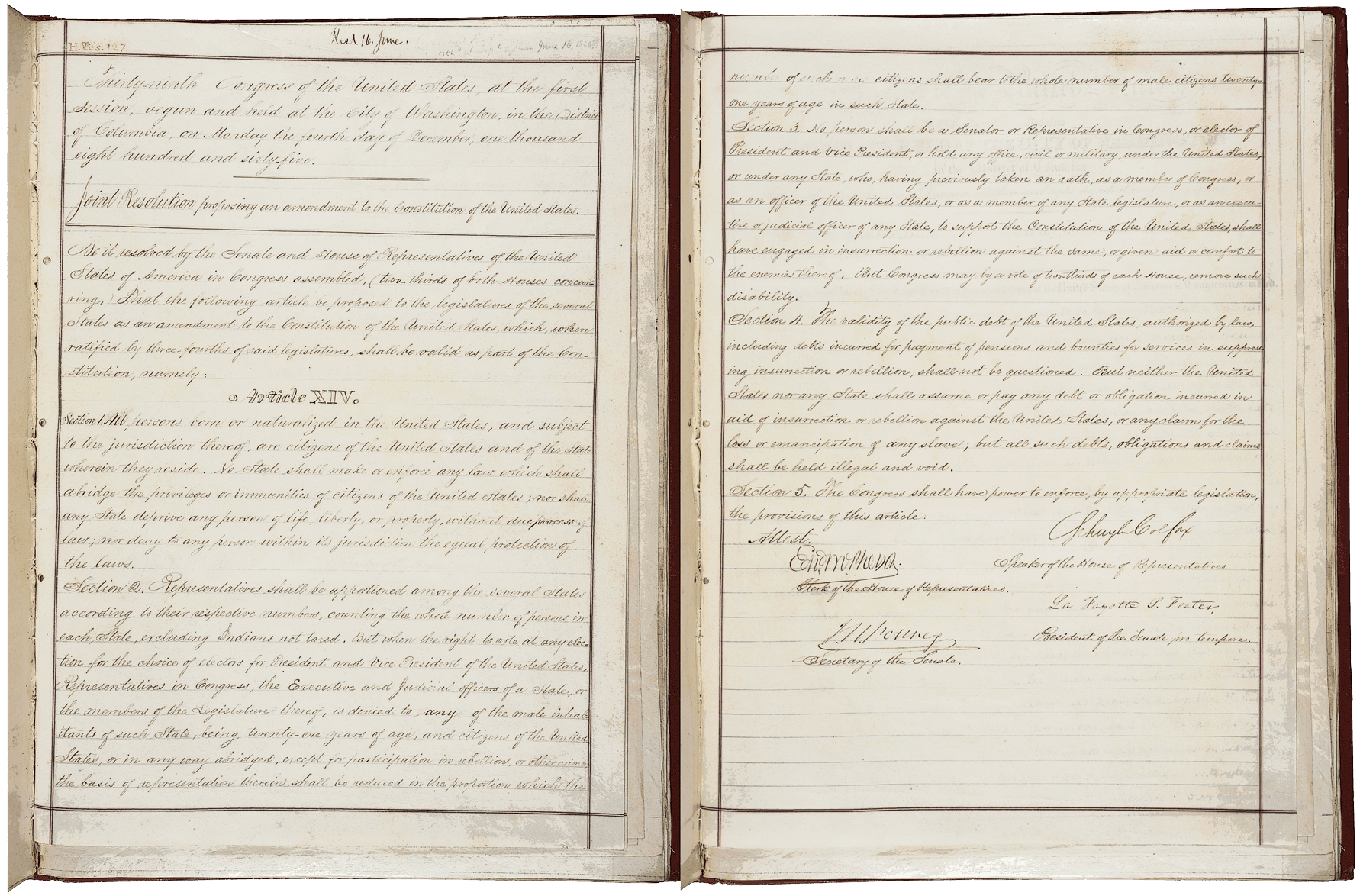

Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, was intended to prevent former Confederates from taking office.

Former Colorado state legislator, Republican Norma Anderson, and other state voters argue that its wording also applies to the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

More specifically, they argue that President Trump is an “officer of the United States,” who engaged in the type of insurrection covered by Section 3.

President Trump has suggested that ballot challenges are altogether inappropriate given that Section 3’s wording bars someone from “[holding] office,” not running for it.

Feb. 8 and Beyond

Arguing for President Trump on Feb. 8 will be Jonathan Mitchell—one of former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s clerks and Texas’ former solicitor general.

Mr. Mitchell has argued before the Supreme Court many times and has been credited with the controversial enforcement mechanism in Texas’ heartbeat law, which the top court allowed to proceed after a challenge in 2021.

Both sides will have 40 minutes to argue their respective cases.

For the respondents, Colorado Solicitor General Shannon Stevenson will have 10 minutes to represent Secretary of State Jena Griswold’s case and the remaining 30 minutes are allocated to Jason Murray, who represents the voters.

President Trump is arguing not only that multiple aspects of Section 3 don’t apply to him but that the Colorado courts mishandled his case.

President Trump appeared at the courthouse for his immunity hearing before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit on Jan. 9. However, CNN reported that he isn’t expected to attend the Supreme Court hearing on Feb. 8.

In the appeals court, President Trump argued that the legal doctrine of presidential immunity shielded him from prosecution in his Jan. 6-related D.C. trial. A unanimous decision by the appeals court rejected his arguments and held that he isn’t immune.

The immunity case could go before the Supreme Court, and along with the Section 3 challenge, it could throw a wrench in President Trump’s already volatile schedule heading into the November election.

The stakes of the justices’ decision are unusually high. A powder keg of major court decisions, campaign politics, and a gridlocked Congress could explode into civic unrest.

Among the Supreme Court’s various legal options is sending the Section 3 issue in some way back to the states or telling Congress to intervene.

The Mr. Foley, et al, brief urges decisive action.

“This Court stands between the potentially disastrous turmoil that would result and a comparatively peaceful election administered consistent with the Constitution and the rule of law,” the authors wrote.

The Supreme Court regularly livestreams oral arguments, and the hearing is expected to be one of the most widely observed in the court’s history. It’s also likely to be one of the most consequential, given the justices’ apparent need to address relatively novel legal questions.

How they will resolve those questions is virtually impossible to predict, but here are some general directions the justices could take.

1. Trump Is Disqualified Under Section 3

Observers have indicated to The Epoch Times that upholding Colorado’s disqualification is the least likely conclusion for the Supreme Court, which is composed of a 6–3 conservative majority that includes three justices appointed by President Trump.

It’s unclear what disqualification would look like in practice. The Colorado Supreme Court’s decision applied only to the state’s primary ballot but, as rulings in Michigan and Minnesota have indicated, challenges could also be brought at a later date regarding general election ballots.

Either way, disqualifying President Trump from ballots would be a dramatic turn of events that would shake the foundations of America’s constitutional democracy in a way prudential and incremental justices are wont to avoid.

Doing so would prevent millions of Americans from directly voting for President Trump, who is the presumptive GOP nominee and has led President Joe Biden in many head-to-head matchups.

Democratic principles were the foremost concern presented in President Trump’s most recent briefing submitted to the Supreme Court on Feb. 5.

The brief began by quoting President Abraham Lincoln’s remarks in the Gettysburg Address: “In our system of ‘government of the people, by the people, [and] for the people,’ the American people—not courts or election officials—should choose the next President of the United States.”

Much of the disqualification case surrounds whether President Trump effectively removed himself from the democratic process by “[engaging]” in an “insurrection”—a conclusion reached by a Colorado district court and affirmed by the state’s supreme court.

President Trump’s Feb. 5 brief argued that the disqualification effort failed to clear several legal hurdles for proving just the “insurrection” provision. Proving an insurrection entails not only showing that Jan. 6, 2021, was an insurrection under Section 3 but that President Trump had actually “engaged” in one as contemplated under that provision.

Many observers have also noted that despite assigning President Trump responsibility for events on Jan. 6, special counsel Jack Smith hasn’t charged him with the federal statute (Section 2383) banning insurrections.

In his dissent to the Colorado Supreme Court decision, Justice Carlos Samour noted: “This is the only federal legislation in existence at this time to potentially enforce Section Three. Had President Trump been charged under section 2383, he would have received the full panoply of constitutional rights that all defendants are afforded in criminal cases.”

Professor Josh Blackman previously indicated to Click2Houston that crimes such as insurrection and treason are harder to prove.

The Supreme Court may also weigh arguments that Section 3’s threshold for engaging in an insurrection is lower than convicting someone of that crime under federal law.

Ms. Anderson cited an opinion by former Attorney General Henry Stanbery, who served in President Andrew Johnson’s administration in the 1860s.

“He wrote that ‘engaged in’ does not require ‘actually [levying] war or [taking] arms,’ but covers any ‘direct overt act, done with the intent to further the rebellion,’” Ms. Anderson’s brief states.

In a lengthy November 2023 opinion, Colorado District Judge Sarah Wallace argued that President Trump effectively used coded language that incited or approved an insurrection. Her ruling stood in contrast with dozens of other Section 3 lawsuits around the country. Nearly all other cases have either failed or been voluntarily dismissed, according to Lawfare, which is tracking the issue.

In disqualifying President Trump, the Supreme Court would be siding with a very small number of judges. A favorable decision for Trump could also galvanize the political left, which has been calling for sweeping court reforms and applying heavy scrutiny to the justices’ ethical judgment.

On its own, a narrow ruling that President Trump engaged in insurrection isn’t enough to disqualify him. However, it would provide fodder for officials like Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows, who cited the Colorado Supreme Court ruling in her determination that President Trump couldn’t appear on the state’s ballot.

It’s also unlikely that the court will issue such a ruling without deciding whether President Trump meets another critical requirement within Section 3—namely, that he’s an “officer of the United States.”

2. Trump Not an ‘Officer of the United States’

Perhaps the best outcome for President Trump is a Supreme Court ruling that he isn’t an “officer of the United States.” This would presumably prevent state courts from applying Section 3 to him at all, cordoning off a whole subset of litigation that could disrupt his campaign.

Heritage Foundation Vice President of the Institute for Constitutional Government John Malcolm told The Epoch Times that along with deciding that Section 3 isn’t “self-executing” (enforceable by courts without prior congressional action), the officer argument is one of the “neatest and cleanest arguments” the court could use in deciding the case.

Despite Judge Wallace’s lengthy consideration of whether President Trump incited insurrection, she ended her opinion by concluding that Section 3 doesn’t apply to presidents.

President Trump’s legal team has argued that prior court decisions and the internal logic of the Constitution show that he couldn’t possibly be considered an “officer of the United States.”

Article II, which promulgates the executive branch, contains three clauses—appointments, commissions, and impeachment—that arguably distinguish the president from the “officers” that he appoints.

The impeachment clause reads: “The President, Vice President, and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed …”

From a textual standpoint, Section 3’s very long first sentence hinges on whether a person seeking the presidency or other offices had sworn an oath to “support the Constitution.”

Ms. Anderson argued that a plain reading of “officer” indicated that the term referred to “all those who hold a federal office requiring an oath.”

“Ordinary parlance should prevail over ’secret or technical meanings that would not have been known to ordinary citizens in the founding generation,’” one of her briefs reads, citing the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller.

Ms. Anderson’s brief also points to historical statements purportedly suggesting that the president is an “officer of the United States.”

She noted that Mr. Stanbery “rejected Trump’s linguistic hair-splitting” by stating that an officer of the United States was “‘without limitation,’ any ‘person who has at any time prior to the rebellion held any office, civil or military, under the United States, and has taken an official oath to support the Constitution of the United States.’”

While Judge Wallace weighed Mr. Stanbery’s statements heavily in designating Jan. 6, 2021, an insurrection, she argued that “the more obvious reading” of Mr. Stanbery’s statements about “officers” was intended to clarify that Section 3 encompassed “all lower-level federal officers.”

President Trump’s Feb. 5 response brief also countered that “no proclamation, floor statement, or court opinion can overcome the fact that elected officials—including the President, Vice President, and members of Congress—cannot be characterized as ‘officers of the United States’ because (1) They are not commissioned by the President; (2) They are not ’appointed‘ pursuant to Article II; and (3) They are excluded from the ’civil officers of the United States’ described in the Impeachment Clause.”

While the Supreme Court hasn’t ruled on Section 3, other court decisions have indicated differing interpretations of what the Constitution means by “officer of the United States.”

Former Federal Election Commission member Hans von Spakovsky, for example, pointed to the Court’s 1888 decision in U.S. v. Mouat and a more recent decision in which Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts said “the people do not vote for ‘Officers of the United States.’”

Washington University in St. Louis law professor Andrea Katz disagreed.

“You can find cases that have held certainly to the contrary,” she told The Epoch Times, pointing to Lucia v. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Quoting a prior court decision, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan said in 2018 that an officer “must occupy a ‘continuing’ position established by law, and must ‘[exercise] significant authority pursuant to the laws of the United States.’”

3. Congress Needs to Weigh In

The 14th Amendment differs from others in how much authority the text gives Congress over its implementation.

Section 5 of the Amendment allows Congress “to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” Section 3 also contains a clause allowing Congress to remove disqualification—or “remove such disability”—by “a vote of two-thirds of” the House and Senate.

But as with other provisions in this dispute, it’s unclear what exactly that language means in practice. Congress’s power over the amendment has spawned several lines of argument regarding Section 3’s applicability to President Trump.

Mr. von Spakovsky, who also manages The Heritage Foundation’s Election Law Reform Initiative, has said that “there’s a very strong argument that Section 3 legally doesn’t even exist anymore.”

He suggested that Congress already removed Section 3’s “disability” by passing laws in 1872 and 1898 granting amnesty to former Confederates.

Two law professors—William Baude of the University of Chicago and Michael Paulsen of the University of St. Thomas—disagree. They penned a paper last year arguing that “Section Three remains an enforceable part of the Constitution, not limited to the Civil War, and not effectively repealed by nineteenth century amnesty legislation.”

President Trump’s arguments in his Supreme Court case may also bear on his presidential immunity appeal and vice versa. His attorneys argued that the Senate already resolved the “insurrection” question when it acquitted him of an article of impeachment alleging incitement of an insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021. The D.C. appellate court rejected that argument but it could face different scrutiny at the Supreme Court.

Entangled in determining whether President Trump committed an insurrection is a question of whether Congress, rather than the courts, should determine whether a bona fide insurrection took place.

There are also questions as to whether Section 3 is “self-executing”; in other words, whether courts can even issue a ruling disqualifying candidates without prior action from Congress.

President Trump has argued that courts may execute Section 3 but only according to methods outlined by Congress.

Ms. Anderson contended that Section 5’s wording doesn’t explicitly preclude states from enforcing the amendment. President Trump had been disqualified since Jan. 6, 2021, and Congress could remove that disability, she said.

“To ‘remove’ something necessarily implies taking away something that already exists,” she said.

4. Colorado Judges Erred

The most narrow decision and likely avenue for prolonging the issue is one in which the Supreme Court merely challenges the Colorado judges’ handling of the case.

In that situation, the justices could theoretically remand the decision to a state court for further deliberation, leaving open the possibility of yet another Supreme Court challenge.

It’s also possible the justices could cite Colorado law in striking the state court’s disqualification.

Both of those options would presumably allow other state courts, legislatures, and secretaries of state to issue decisions removing President Trump from their ballots.

President Trump’s petition to the Supreme Court focused mostly on Section 3’s applicability to him. However, he did accuse the state Supreme Court of violating the Constitution’s electors clause, which vests state legislatures with the power to choose individuals who decide the president through the Electoral College.

It did so by flouting the Colorado Legislature’s guidelines for challenging a candidacy in court, his petition argues.

Raising due process concerns, President Trump criticized Judge Wallace for bypassing the statutory deadline for holding a hearing on Ms. Anderson’s and other voters’ petition challenging his candidacy.

His petition also cites Justice Samour’s dissent, which described the lower court’s litigation as falling “woefully short of what due process demands.”