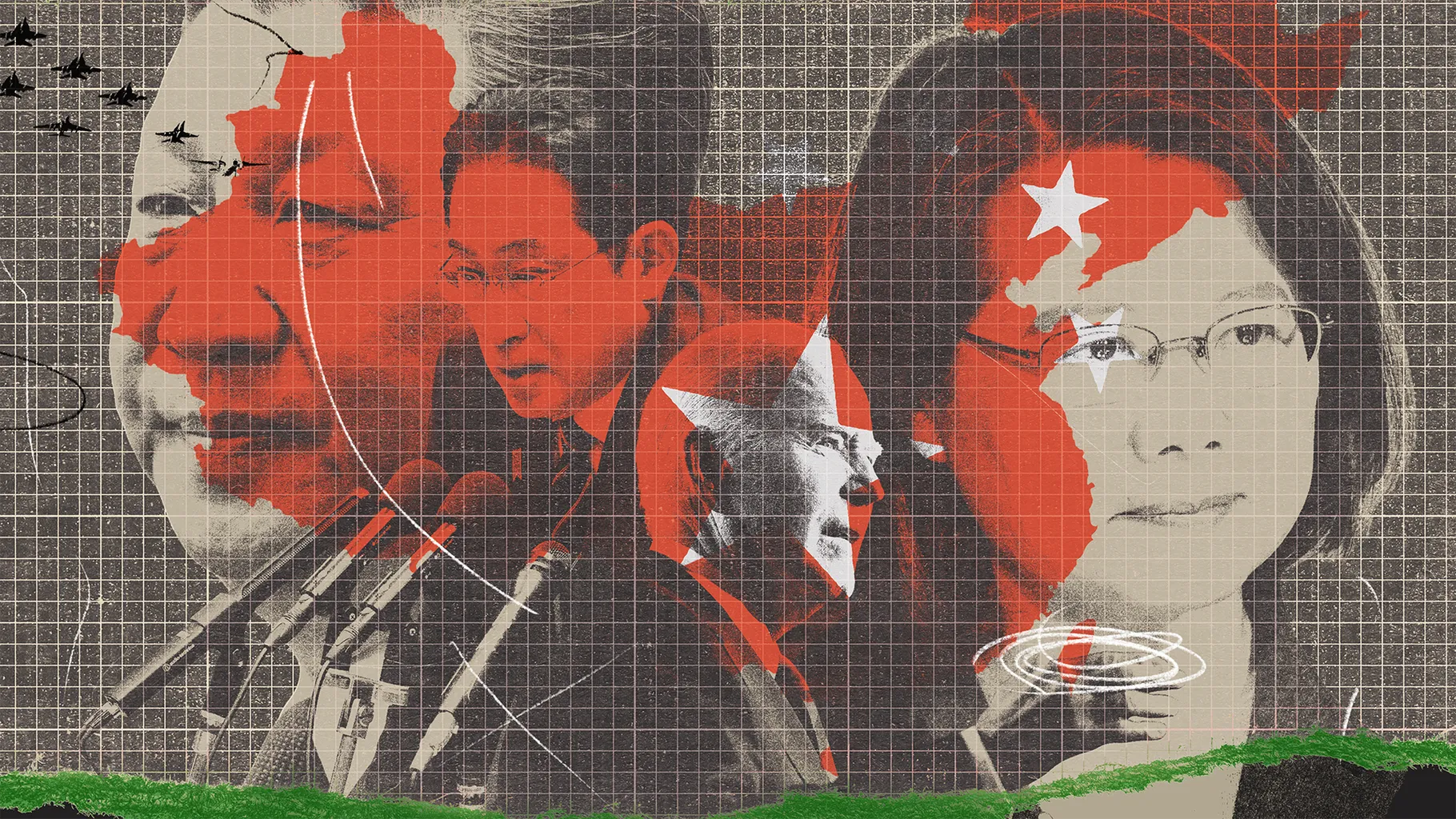

If China were to invade Taiwan, the American response could depend on its key ally.

TOKYO, Japan — If we’ve got to pick a year, it’s 2027. Imagine China is harassing Taiwan with near-constant flyovers of fighter jets and drones. Beijing has increased the frequency and scale of its amphibious exercises, so much so that it is getting hard to know what is a run-of-the-mill military drill, and what might be the start of the real thing: a full-scale invasion of Taiwan.

Because in this hypothetical future, the real thing is looking increasingly possible.

In it, Chinese leader Xi Jinping has spoken with urgency about the country’s “national rejuvenation” — that is, when Taiwan, which China views as a separatist province, is “reunified” with the mainland. The United States and its allies are promising an unwavering response to any Chinese military escalation, without saying exactly what that entails. Taiwan says it seeks peace, but will defend itself from attack if necessary. US and Chinese diplomats are shuttling through Singapore, and Bali, seeking an offramp, even as US intelligence suggests Xi wants to act, and act now.

Then, Xi does. A massive cyber assault overwhelms Taiwan’s networks, immobilizing critical infrastructure. Chinese ships sever Taiwan’s undersea cables, and with it communication among its islands. Missiles strike Taiwanese government and military sites, the opening salvo to the large-scale amphibious assault that China was practicing in full view of the world.

The United States will now have to decide if the promised unwavering response means defending Taiwan. If the president and Congress decide yes, America’s national security interests demand a US military intervention, then he (because it’s probably still going to be a he) has another call to make. This one is to Japan, the US’s key ally, to ask some version of the question: Will you let us use our military bases?

On the other end of the line is the Japanese prime minister, who knows that the US has tens of thousands of troops stationed at 85 military facilities on Japanese territory, a foundation of the security alliance between the two countries. Who also knows China has a likely arsenal of some 1,000 medium-range ballistic missiles that could target those US bases, and by extension, the cities of Japan and its 127 million citizens. Who knows that Japan’s westernmost island is only about 70 miles from Taiwan. Who knows that whatever decision he or she makes, it could very well decide the outcome of any war before it’s barely begun.

What does Japan do?

Like it’d tell you now.

Why Japan may be the key to any real war over Taiwan

It is not 2027. Even if it were, it is not a foregone conclusion that China would be ready and willing to mount a costly full-on invasion of Taiwan by then. If you ask plenty of sober-minded experts today, it’s not even highly probable. Xi reportedly told President Joe Biden in November that China did not have a plan for military action in Taiwan in 2027 or 2035.

So maybe it won’t happen in the 2030s, or even the 2040s or by 2050 — some of the other estimates floating out there as to when China could attack Taiwan. Ideally, China would never. China has said that it seeks a “peaceful reunification,” though they have not ruled out achieving one by force.

Even then, a full-scale invasion may be the most extreme of all courses — there are plenty of ways China can use force or coercion against Taiwan that fall short of a storming-the-beaches-style assault. But Xi has made clear his vision of China is incomplete without Taiwan. “The reunification of the motherland is a historical inevitability,” he said in his recent New Year’s address.

Taiwan increasingly opposes unification with China, and the majority of people in Taiwan want to preserve a version of the status quo. Lai Ching-te won Taiwan’s January presidential election on a platform of preserving Taiwan’s democracy and sovereignty, and that is likely to keep Taipei moving closer to Washington than Beijing. US and China relations may have thawed a bit since their spy balloon nadir last year, but both US parties see China’s rapid-paced military buildup and geopolitical ambitions as a threat to America. The Biden administration has cultivated and deepened its partnership and security ties in the Indo-Pacific, and though it may not say so explicitly, it certainly looks like a coalition to deter China.

Which is why, even if an invasion is unlikely, or even decades away, the question — What might Japan do if China invades Taiwan, unprovoked? — has become more urgent. Japan’s answer could shape how the US prepares for any armed confrontation over Taiwan, its outcome, and whatever world emerges after.

Whether it wanted to or not, Japan itself cannot intervene to defend Taiwan. Japan’s post-World War II constitution renounces war, and so its Self-Defense Forces (SDF) are just that, a military that exists to defend its territory. (Japan has, especially in recent years, pushed against those constitutional parameters.)

What Japan does have is a security alliance with the United States. This treaty commits the US to defend Japan in the event of an attack on its soil, in exchange for America’s use of Japanese territory for “the purpose of contributing to the security of Japan and the maintenance of international peace and security in the Far East.” That is, military bases. About 55,000 US forces are based in Japan, and US military facilities span 77,000 acres, the majority in Okinawa prefecture. In any war with Taiwan, the US would need to deploy naval vessels and fighter jets from these locations.

But the use of these military bases requires prior consultation: Japan must grant the US permission to use these facilities in combat beyond the defense of Japan. If Taiwan invades, and the US wants to intervene, Japan has its own dilemma: to say yes potentially signs Japan up for war, leaving itself vulnerable to attack from China. To say no could unravel the US-Japan alliance, leaving itself vulnerable by cutting off its only security guarantor.

If Japan does say no, seeing the risks to itself and its population as too great, in any fight with China, the US is probably toast. The American military would likely be crushed if it intervened without being able to deploy its assets from Japan, but potentially strategically defeated if it did not intervene at all.

“China succeeding in taking over Taiwan should mean the US is out, which means Chinese hegemony, at least in this region, is expanding,” said Yoshihide Soeya, professor emeritus of international relations at Keio University. “That would mean that Japan would have to think of the national strategy to live under such Chinese influence, and I don’t know if under that scenario, if the US-Japan Alliance is still there. Maybe not — and then it’s a totally different world.”

Even if Japan says yes and lets the US use its bases, it is no guarantee of an unchanged world. Some of that may depend on exactly what type of affirmative answer Japan gives. It could just grant access to the bases and attempt to remain out of the battle — though that may be as much China’s decision as Japan’s. In addition to granting that access, Japan could choose to provide logistical or operational support to the US from the start. That’s an outcome that some wargames, including one published last year by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), suggest would considerably improve the US and its allies’ fortunes, giving them a chance to fend off China. But it would come at costs and heavy losses, for the United States and for Japan.

“The question is: Would we be willing to sacrifice ourselves to defend Taiwan?” said Narushige Michishita, executive vice president and professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) in Japan.

“That’s partly why — although I think Japan is severely becoming more committed to the defense of Taiwan — Japan has never said, or the government has never, ever said: ‘We will defend Taiwan,’” Michishita added.

“The Japanese government is walking a tightrope.”

How Japan got here

“I myself have a strong sense of urgency that Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow,” Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said in spring 2022.

Japan saw the war in Ukraine as both a wake-up call and an opportunity. Russia’s full-scale invasion rocked the rules-based international order, an order that Japan sees as integral to its own political and economic security interests. Japan also saw its own vulnerability reflected back in Russia’s assault, and it started thinking more seriously about what it might need as a middle power if similarly threatened. “Japan would need resiliency and sustainability. This is the lesson learned from Ukraine,” said Koichi Isobe, a retired lieutenant general with Japan’s Self-Defense Forces.

In December 2022, Japan articulated this vision when it updated its national security and defense strategies and made commitments to significantly expand its defense budget over the next five years. Japan also made plans to invest in counter-strike capabilities as a deterrent to outside attacks.

“Post-war Japan has long refrained from playing or even seeking a role in geopolitics, let alone the military domain,” Soeya said. But these documents focus on that agenda, and put Japan’s defense capabilities as a central component of coping with an unpredictable and chaotic world.

“In terms of emphasis on key elements, it’s a paradigm shift,” Soeya added.

This shift was dramatic, but the foundations were already in place. Japan, especially under former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, had invested more in its military and expanded its defense capabilities and partnerships. The Ukraine war reinforced the reality Japan already recognized: China’s rise, North Korea’s threats, and the US’s rising America First posture meant Japan needed to be proactive about strengthening and protecting its security and interests amid such global instability.

America is Japan’s essential ally. The election of Donald Trump did not undo it, so much as convince Japan that it needed to prepare for a world where America was more isolationist, more unpredictable, and a weaker power, especially against an ascendant China. Japan would need to get better at defending itself. And it probably needed to hedge and foster bonds with other like-minded countries in the region and beyond — like deepening ties with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). All of this wasn’t — couldn’t be — a strategy to replace the US. In preparing to fight for itself, Japan was equalizing the partnership a bit more, showing the US how much more of a capable, and essential, partner it could be.

“I say this more dramatically than literally,” US Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel told Vox in November about both the US and Japan national security strategies, “but we could have written theirs, and they could have written ours. That’s how closely aligned they are on North Korea, China, the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait. [They’re] just incredibly complementary documents.”

“I think we’re at the first iteration of a new chapter called alliance projection, and closing the chapter on alliance protection,” Emanuel added.

These 2022 security documents (in total, three major ones), were an official coming out for this long-building policy. And in them, many saw that Japan was more obviously preparing for the potential it might be drawn into a war. “To me, it’s vividly clear that Japan is changing its course and getting committed to the defense of Taiwan,” Michishita said.

Japan getting more committed to the defense of Taiwan is not quite the same as an actual commitment. Japan has an interest in “strategic ambiguity,” as does the United States, which also tries (and sometimes fails) to pursue a similar course on Taiwan. But Japan’s defense investments and new national security strategy are a sign it knows it needs to prepare for a possible Taiwan emergency.

The United States is central to all of it. Many current and former government and military officials told me Japan recognizes that this current security order is tenuous — but it still sees it as the best one it’s got. Which is also the strongest case for Japan granting permission to the US to use its bases. Otherwise, it all goes away.

“If the US requests for support from Japan, and if Japan turns it down, then the Japan-US alliance will collapse,” said Kyoji Yanagisawa, director of the International Geopolitics Institute Japan and former defense official who served decades in the Japanese government.

This is also why many see the idea that Japan could somehow sit out a Taiwan conflict implausible. “[A] Taiwan war is our war,” said Nobukatsu Kanehara, of Doshisha University, and former top adviser to Shinzo Abe.

Japan’s territory would be too close to the conflict, leaving it vulnerable, both to potentially being caught in the crosshairs — or as a future target. China might want to expand, Isobe said, and it “might not stop at Taiwan.”

Hirotaka Yamashita, a retired lieutenant general with the Ground Self-Defense Forces, pointed out that thousands of Taiwanese civilians will likely still seek to evacuate to safety, including to the islands that lay between Taiwan and Japan, on fishing boats, commercial vessels, or motor boats. A Chinese takeover of Taiwan, said Isamu Ueda, a Komeito representative and member of the committee on foreign affairs and defense in the Japanese legislature, will affect Japan, physically and economically — Japan, like so much of the rest of the world, is reliant on semiconductors and other supply chain inputs from both Taiwan and China. “It will destroy the international order in East Asia and in the Pacific region,” he said.

All scenarios Japan wants to avoid. But it may still not avoid them, even if it grants US access to its bases. “Is Japan going to accept the missiles coming over to Japan in order to maintain the alliance — or to have the alliance collapse by turning down the request from the US?” Yanagisawa said.

Japan’s domestic politics are the big unknown

If this all happens — if China launches an assault on Taiwan, if the US wants to intervene, if the missiles start flying — Japan will have to decide about the US bases. The US and Japan, as allies, will probably have talked about this scenario a lot, so Japan’s response probably won’t be a total surprise. But planning and preparations are one thing, the imminent threat of missiles landing on your territory is another. And any Japanese leader will ultimately have to decide whether to sell the public on the potential for inviting war against Japan.

The military wargames may seem complex, but the political ones are even more so. The Japanese public has broadly negative views of China, but getting into war with Beijing is another issue. A recent survey conducted by a Stanford researcher showed that support for Japanese involvement in a Taiwan emergency declined if China promised not to attack Japan. Plenty of officials and military experts pointed out to me it would be foolish to trust China. And support for any Japanese military involvement increases if China threatens Japan, or any of its outlying islands. But the tradeoff that a Japanese leader has to make is a possible future threat of war versus an imminent one.

China is likely to be aware of this and may even be starting to try to sow these fears. A Chinese propaganda video last year appeared to threaten Japan with nukes if it sought to defend Taiwan, a particularly potent threat given Japan’s history.

Many experts and officials I talked to thought this was a huge reason why Japan was walking this tightrope on the Taiwan emergency question: There is likely a huge gap between what the political elites believe, and what the public sees. “Japanese politicians, when talking about defense policies to the public, they always say that we are buying missiles to protect people’s lives,” Yanagisawa said. “But that’s wrong because national defense is essentially the people costing their lives to defend their country.”

“That narrative lacks reality,” he added, “so I’m really worried what is going to happen when Japan is in an emergency.”

The Japanese public most aware of the trade-offs are likely those already familiar with the US presence. The majority of US military facilities are in the islands of the southern Okinawa prefecture, where public disapproval of military bases is as high as 70 percent. US officials have tried to take steps to change that. But it remains true that people in these areas, which are most at-risk in Japan given their proximity to US facilities, are also those who already have a skeptical view of the US presence — and it’s unclear how that may sway over Japan’s larger national security decisions.

Are we asking the right questions about Taiwan — and Japan?

Asking what Japan might do if China invades Taiwan is a bit of a black-and-white question in a situation that has few of them. There is a whole range of options between the current status quo and a full-scale invasion. China could potentially seize an outlying Taiwanese island — think Russia in Crimea in 2014. Beijing might keep at its gray-zone tactics or attempt a blockade. Tensions could escalate, and maybe there’s a miscalculation or unintentional confrontation between the US and China that leads to a larger standoff. Even in an invasion, the politics, the leaders, the timing, what is happening in the rest of the world — all of it will shape the answer to that question.

Still, many experts and current and former officials I spoke to, both in Japan and the US, believe Japan’s stance on Taiwan is still a question worth asking. You plan and prepare for war so you don’t have to go to it — and knowing what kind of war it might be enhances both. “If your goal is to deter, you need the capability plus the credibility,” said retired US Rear Admiral Mark Montgomery. “The belief that Japan will be an active participant in combat operations is a really big element in this in a positive way.”

If Japan is going to at least grant access — which is, on the whole, experts’ most common response — then many thought both the US and Japan should take greater steps to prepare for it. In some ways, Japan is: In December, Tokyo approved an increase in its military budget and loosened a ban on lethal weapons exports, which will allow Japan to better coordinate on a couple of key weapons systems with the US and may also help boost the country’s defense industry. Japan is also developing a fighter jet with Italy and the United Kingdom.

At the same time, many experts pointed out that as ambitious as Japan’s moves may be, it’s still very much unclear whether the defense spending is enough if Japan’s military is drawn into a conflict over Taiwan. Spending alone also isn’t enough: It would also require thinking about what you might need to fight a war alongside the US, such as improving interoperability or communication between forces, and hardening infrastructure on military bases and civilian infrastructure to protect against Chinese missiles. Quiet initiatives are happening, for example, to get Japanese civilian shipyards to repair US naval ships, which saves money now, but would be very handy in the event of a conflict.

Yet deterrence is itself a tricky and unpredictable calculation. The more committed, the better the credibility. But it can also be an accelerant, entrapping countries on a path to miscalculation, and war. “My frustration has to do with the fact that if you’re worried about those worst-case scenarios, then that should motivate you to move in the other direction — trying to talk about and think about efforts to prevent this collision course from nearing realization,” Soeya said.

And if the collision course is realized, if China and the US do go to war over Taiwan, no choice Japan makes will single-handedly solve it. But all parties do have an interest in preventing it.

“There is no winner or loser in a war,” said Yamashita. “What is left is only the destroyed land and damage to people like what we see today in Ukraine and Israel. A Taiwan emergency needs to be averted.”

This reporting was made possible by a grant from the Foreign Press Center of Japan.